The Monster of Cannock Chase

The horrific story of a child killer who competed in prison with Moors Murderer Ian Brady over who was the most notorious.

The Burning Car

On March 28, 1969, a team of mechanics working for Black Country car dealer John Hart rolled the latest addition to his stock onto a nearby forecourt.

A small crowd began to gather, and Mr Hart instructed his men to smash the windows and lights with pick-axe handles, before soaking it in petrol.

Then Mr Hart, owner of Queen’s Cross Garage in Dudley, lit a torch, and ceremonially tossed it inside the car, setting light to the upholstery. Within minutes, the gleaming grey Austin Cambridge he had bought for £195 the previous day was engulfed in flames, and a pillar of black smoke was rising above it. Traffic ground to a standstill while stunned passers by stopped to watch in disbelief.

“I think that was £195 well spent,” said Mr Hart, adding that his mother-in-law had telephoned him expressing her gratitude that the car would be destroyed.

The car in question had previously belonged to ‘Cannock Chase Murderer’ Raymond Morris, a serial child killer who at that time vied with Moors murderer Ian Brady for the title of most hated man in Britain. Five weeks earlier Morris had been jailed for life for the murder of seven-year-old Christine Darby and the attempted abduction of 10-year-old Margaret Aulton. Screams of “hang him!” rang out from a 200-strong crowd which had assembled outside the court building in Stafford.

The grey Austin was the car Morris had used to lure Christine to her death, and would become a crucial piece of evidence in his conviction. But detectives believed this was just the tip of Morris’ offending. He was also considered to be responsible for the unsolved murders of five-year-old Diane Tift and six-year-old Margaret Reynolds, as well as the abduction of nine-year-old Julia Taylor. And while serving in HMP Preston, he was reported to have become involved in a sick rivalry with fellow child killer Brady, the clashes often ending in violence as they argued about who had the greater notoriety.

Incredibly, Morris carried out his reign of terror in plain sight, while leading a double-life as a well-respected member of society in a block of flats opposite Walsall police station.

Detective Constable Trevor Lowbridge, who interviewed Morris following his arrest, recalled being struck by his steely, calm presence.

“He was cold, calculated and icy the whole time,” Mr Lowbridge told the Express & Star.

The detective had been assigned to play the role of “good cop” in the interview, hoping it would entice Morris to talk. But Mr Lowbridge found it impossible to build up any kind of relationship with the killer.

“I asked his name and he just looked at me, he just had vague, staring eyes,” he said.

“It might have been four or five seconds but it seemed like a minute and a half, before he replied ‘I’m Raymond Morris.’

“There was this big silence again when I asked him where he lived, so you just couldn’t build up any rapport at all. He never gave me the impression that he was a friendly sort of person.”

Unflappable

He was described as a good-looking, immaculately dressed and well-spoken man of great intellect, but his urbane appearance and self-assured demeanour also betrayed a self-confidence bordering on arrogance. This would prove to be his Achilles heel, leading him to make a number of casual slip-ups which would ultimately bring about his downfall.

Probably the most famous of these took place the moment he abducted Christine. He let his mask slip by asking directions for Caldmore Green, using the correct, but little-known, pronunciation of “Calmer”. This immediately alerted police to the fact that the killer was either from Walsall, or had close links to the town.

His fondness for flashy-looking cars also began to draw attention to his activities. And inexplicably, when Morris was arrested, an officer complimented him on his stylish Ford Corsair – prompting the killer to reveal he had previously owned a grey Austin Cambridge, the car Christine’s killer had used. The reason why he volunteered such crucial information remains a mystery, but it convinced officers they had got the right man.

Ray Morris was born in the Ryecroft area of Walsall in 1929, growing up with an older sister, Eileen, and younger brothers Peter, Geoffrey and Norman.

Peter remembered his brother as being totally unflappable, even as a child, never shedding a tear and never losing his temper.

“We had a very strict upbringing and, no matter what happened, he never cried,” said Peter.

“He could get on with anyone, and anyone could get on with him.”

His brother recalled him being a talented painter and musician, who could play many instruments, and who had a painting displayed on the wall of a Walsall pub.

But while he was undoubtedly a clever youngster, his academic career was not especially distinguished, attending North Walsall Secondary School.

After leaving school, he worked as a pattern maker at Hope Works in Pleck Road, where he met Muriel, a teenager two years his junior. After completing his National Service in the RAF – where he was stationed at RAF Cosford, Bridgnorth and London – he married 19-year-old Muriel at St Peter’s Church, Walsall, on July 28, 1951. They initially lived at Fullbrook Road, Pleck, before moving to a council house in Odell Road, Leamore, and the marriage bore two children.

Muriel painted a happy picture of their early courtship, describing how Morris would write love poems to her while in the RAF. But she recalled how her husband struggled to settle into work on his return from National Service, and started flitting between different jobs.

He continued with his love of painting, though, producing oil paintings and sketches that he framed himself.

“I was quite proud of him,” said Muriel.

She recalled getting on well with Morris’s family, but started noticing that he did not really fit in.

“Ray seemed always to be the odd one out somehow,” she observed. And after their marriage, she began to notice a darker side to her husband.

“He was a good husband, but he was very demanding sexually, and in the end I got fed up of it,” she said.

In 1958 came Morris’ first brush with the law, and police at the time noted the quiet belligerence that would become his hallmark. He appeared before Walsall quarter sessions charged with stealing or receiving an £80 tape recorder, but he calmly fronted the allegations out, and was acquitted.

Muriel said the couple never really fell out, but they separated in 1960, Muriel returning to Fullbrook Road, and Morris staying at the family home in Odell Road.

She suspected by this time that Morris had started seeing someone else, and he coldly told her he saw no future with her and children. Following the separation, Morris wrote to Muriel on a number of occasions, asking her to visit him. The purpose of these visits were so he could continue to have sex with her, and he asked to see her twice a week.

On one of these visits, Morris told her he wanted to see her so he could kill her, although he never actually hurt her. After a few visits, they parted for good, and they were finally divorced in 1964 on the grounds of her adultery.

In August that year, at the age of 35, he married 21-year-old Carol Horsley, who lived next-door to Morris’s parents in Beddows Road, Walsall.

By that time, Morris was living in a fourth-floor flat in the recently built Regent House tower block in Green Lane, about 100 yards from the police station. The couple lived a quiet life behind their yellow front door, Carol working in the wages department at H D Jackson in Hospital Street, Walsall, and Morris working first as a travelling salesman for a company in Sheffield, later switching careers to become an engineer.

Abductions

At 9pm on December 2, 1964, nine-year-old Julia Taylor was lured into a two-tone blue Vauxhall Velox in Bloxwich by a man claiming to be a friend of her mother, and describing himself as ‘Uncle Len’. The man said the child’s mother had asked him take her to aunt’s home to collect Christmas presents. The man took Julie to slag heaps near the mining village of Bentley, and sexually assaulted her before attempting to strangle her, throwing her half-naked from the car into a ditch.

It was by sheer good fortune that a passing cyclist spotted her about 50 minutes later, having heard “weak, sobbing” noises as rode past in pouring rain and darkness. The cyclist immediately flagged down the driver of a passing van, who took the sobbing and bleeding child to hospital.

The man, now presumed to be Morris, had left Julia with grievous internal injuries, and it was estimated that she would have died within 20 minutes from exposure had she not been found.

Julia, also occasionally referred to in the media as Julie, remembered little about her ordeal or her abductor, beyond begging him to take her home when she noticed he had driven past her aunt’s home and his conversation suddenly became more lurid in nature. An eyewitness came forward, however, who gave a detailed description of the car, right down to the two-tone paint finish, small fins at the rear, and a distinctive spot lamp near the driver’s door. The car was never traced, and the crime went unsolved, although it later emerged that Morris owned a car matching that description at the time.

On the afternoon of Wednesday, September 8, 1965, six-year-old Margaret Reynolds was walking the short distance back to Prince Albert Primary School in the Aston area of Birmingham, having spent the lunch break at her home in Clifton Road. Her older sister Susan had walked part of the way, but the two parted company to go to their respective schools.

When Margaret failed to return home from school, it quickly became apparent that she had not shown up for her classes that afternoon, and her parents immediately reported her missing to police.

In the weeks that followed, 160 officers questioned more than 25,000 people around the Aston area. Two hundred posters were distributed featuring a photograph of Margaret, and investigators searched all houses and landmarks within an eight-mile radius of where Margaret was last seen alive.

In the months before Margaret’s disappearance, there had been a number of reports about a man attempting to entice young girls into his car and committing sexual assaults. It later emerged that Morris, who by this time was working as a travelling salesman for a Sheffield based company, had a business appointment in the Aston area close to the time Margaret went missing.

On December 30, 1965, three months after Margaret’s disappearance, five-year-old Diane Tift also disappeared on the five-minute walk home from her grandmother’s house in the Blakenall area of Walsall. At about 3pm, Diane left her grandmother’s home in Chapel Street, walking about 400 yards to her own home in Hollemeadow Avenue. She was carrying a pink plastic handbag with a white plastic strap she had received as a Christmas present. A relative believed she had seen Diane walking past a nearby laundrette along the route home.

Concerned that their daughter had not arrived home, Diane’s parents Terry and Irene Tift reported her missing at 7pm. More than 2,000 people volunteered to join the search for her, but as was the case with Margaret, she appeared to have vanished without trace.

Within three days of Diane’s disappearance, more than 500 officers from across the region had been assigned to the search. Officers, concerned that a serial killer could be on the loose, tentatively linked the case to that of Margaret Reynolds. More than 6,000 homes, gardens and outhouses around the Bloxwich area had been searched within a week of Diane’s disappearance. Officers combed disused factories and warehouses, underwater units searched ponds and reservoirs, but all to no avail.

Then, on January 12, Tony Hodgkiss made a grim discovery while cycling with his nephew past Mansty Gulley on Cannock Chase, between Penkridge and Littleton. Mr Hodgkiss, a 25-year-old collier who lived about two miles away, initially thought the body in a deep waterlogged ditch was a doll. It quickly emerged that the body was that of Diane, who had been raped before being suffocated with the hood of her own coat. And there was worse to come. As police continued to search the site, about three-quarters of a mile from the A34, a second body was found about 300 yards away – the partially decomposed remains of Margaret Reynolds.

A Pattern

By this time a pattern was emerging. Within days of Diane’s disappearance, 10-year-old Patricia Kimberley of Warner Place, Bloxwich, was stopped by a motorist. The driver tried to grab her, but she escaped his grasp and ran home. The previous November, a man tried to lure eight-year-old Lorna Povey, of Lancaster Place, Bloxwich into his car, but she also ran off.

Assistant Chief Constable of Staffordshire Police, Tom Lockley, delivered the grim news at a press conference: “We are hunting a dangerous child killer who may strike again.”

Despite the best efforts of the investigating team, there was no breakthrough, and by the summer of 1967 the investigation had largely ground to a standstill.

Convinced the killer would strike again, Detective Chief Superintendent Harry Bailey, head of Staffordshire CID, drew up a plan that all routes into or out of Walsall would be closed within 20 minutes of any reported child abduction.

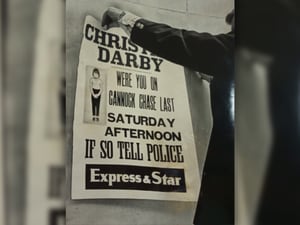

Their fears proved correct. On August 19, 1967, at about 2.30pm, seven-year-old Christine Darby was lured into a grey car as she played with two friends near her home in Camden Street, Caldmore. Christine asked for directions to Caldmore Green, and when given directions, Morris feigned confusion and asked Christine to enter the car and show him the way, promising to drive her back to her friends immediately afterwards. Excited at the prospect of a ride in a car, Christine willingly got into the vehicle, but her friends observed the vehicle reverse, then drive at speed in the opposite direction to Caldmore Green – towards Cannock Chase.

Christine’s friends immediately ran to her home to tell her mother Lillian what had happened, and Mrs Darby went straight to a phone box to contact police, who set up the roadblocks.

Police launched an immediate manhunt and media investigation, distributing 24,000 posters featuring Christine’s photographs around the West Midlands.

The children who were with Christine gave a detailed description of Morris: a white, clean-shaven man in his mid-30s with dark hair, wearing a white shirt and driving a grey car, possibly a “Farina” model Austin Cambridge or Morris Oxford. And they noticed that he spoke with a local accent. Seven-year-old Nicholas Baldry was very specific that he pronounced Caldmore Green as “Calmer Green”, meaning he was almost certainly from the vicinity. The investigating team decided to focus its investigations on the Walsall area.

As a result of the publicity blitz, one eyewitness told police he had seen a grey car travelling in the direction of Cannock Chase shortly after 2.30pm on August 19. Notably, he said he saw a dark-haired girl in the passenger seat.

The following day, police began a thorough search of Cannock Chase. This was no small feat; the chase covered about eighty-five square miles, a third of this covered with forestry, clay pits and coal mines.

More than 300 police began searching Cannock Chase on foot, starting around Pottal Pool, close to where Margaret and Diane had been found. They were quickly joined by more than 200 officers from neighbouring forces, and 250 soldiers from the Staffordshire Regiment. Within hours, an item of children’s underwear was discovered, and a child’s pump was found three miles from this location.

The Investigation

Then, on the afternoon of August 22, soldier Michael Blundred found Christine’s sprawled, partially naked body while searching a cluster of trees managed by the Forestry Commission, about a mile from where Margaret and Diana had been found. Christine had been sexually assaulted and then suffocated.

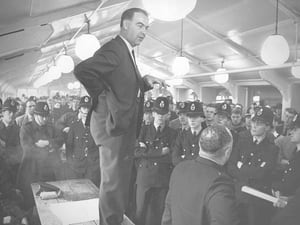

Standing about 100 yards from where Blundred found the body was 17-year-old Alan Parker, a police cadet who had ‘lied’ about his experience with the force so he could help out. On the morning of August 22, dozens of officers and cadets were summoned to the parade room at Walsall police station, and the officer in charge told anybody with less than six months experience to leave the room.

“I stayed where I was, even though I’d only joined the force three months before, because I badly wanted to be part of the investigation,” Mr Parker told the Express & Star in a 2014 interview.

“I first knew Christine Darby had gone missing when officers stopped a double-decker bus I was on a day or two before.

“I was on my way to Walsall when the bus was pulled in by the old flour mill on Wolverhampton Street and an officer got on and showed all the passengers a picture of Christine and asked if we had seen this girl. You could see people thinking ‘not again’.”

“We stopped for a briefing at a big hall involving everyone on the search, including the Army. There were probably 500-600 of us.

“It was so packed, I listened with some others at an open window outside. There was a light aircraft and a helicopter flying low overhead.

“Then we set off into the densest part of the Chase. I ruined my new uniform as many others did that day because under the bracken and fern was old fencing with rusty barbed wire which cut my legs and ripped my trousers. Everyone had whistles and we were told to blow them if we found anything. I blew mine a couple of times because you would come across bits of clothing.

“Everything stopped while an officer came across to inspect what you’d got. Then he would give two blows on his whistle to signal for everyone to carry on.”

While the hunt was in progress no-one had eaten or drank anything, not even water. Mr Parker remembers officers flagging down a Banks’s beer lorry and commandeering all the soft drinks and crisps aboard to share among the exhausted search crew. “Everything was taken but the beer. I presume the brewery was reimbursed.” There wasn’t enough to go round so I shared a bottle with a couple of others.”

A detailed examination of the crime scene the following morning revealed fragmented tyre tracks, which showed a family-sized saloon car had driven close to where the body was found. An expert from the Pirelli tyre company showed said the car had performed a manoeuvre which suggested the driver was ‘one of considerable skill and experience’.

Investigators began the laborious task of identifying and eliminating all individuals and vehicles seen on Cannock Chase on the afternoon in question, quite a job in the pre-computer age. Over the following months, the owners of more than 600 vehicles observed on the Chase were traced and eliminated,

Two individuals who had been on the Chase on the afternoon of August 19 reported seeing a grey car, driven by a man with dark hair, parked close to the location where Christine’s body was discovered. One of these witnesses, Victor Whitehouse, gave a detailed description of the man, whom he had observed leaning on the door of what he thought was a “Farina” Austin Cambridge or Morris Oxford, matching the description of the car Christine had been abducted in. Mr Whitehouse said he was confident he would recognise the man again. The other witness, Jeanne Rawlings, who saw the car driving slowly close to the scene, was certain it was a Farina Austin Cambridge.

At the time, the Austin Cambridge was one of the biggest selling cars in Britain, and officers began the massive task of tracing every grey Cambridge in the Midlands.

Over the following months, investigators checked 1.375 million files, identifying 23,097 vehicles which needed to be traced. The owners of these vehicles were interviewed, and their alibi on the date of the abduction verified. As each successive vehicle was eliminated from the inquiry, investigators expanded their search radius, gradually interviewing the owners of more than 44,000 cars.

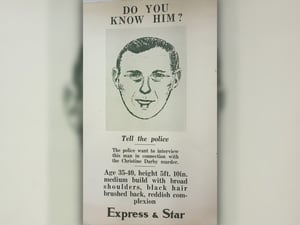

The detailed descriptions of Victor Whitehouse and Jeanne Rawlings were used to create the first colour facial composite of a suspect used in a manhunt in British criminal history.

More than 2,000 copies of this image were distributed across the country, and the response was huge.

At a press conference on October 25, Det Supt Ian Forbes said he was confident the picture was a good likeness of the killer.

“We are convinced that the man who murdered Christine Darby is the man in the Identikit picture and that it is a good likeness.

“His is a face well-known to someone, probably to several people. He is being shielded, either by a relative who knows of his guilt but is prevented from coming forward by misguided loyalty or fear, or by people who recognise a resemblance in an acquaintance but cannot bring themselves to believe that the person could be a child killer.”

Closing in

Meanwhile, just as the investigation was hotting up, Morris briefly found himself in police custody – but slipped through their fingers.

Some time in 1966, following Diane’s murder, Morris had changed career, and began working as an engineer. In his spare time, he was a keen photographer, turning his spare bedroom into a photographic studio. Two schoolgirls, aged 10 and 11, were playing truant and hanging around the factory where he worked, and Morris allegedly offered them two shillings each to go to his flat and undress for photographs. A few days later, the girls told their parents about the incident, and Morris was arrested in October, but a search of his flat proved fruitless, and Morris was released without charge.

In April, 1967, Morris was appointed foreman at Taylor Precision Engineering in Oldbury, where he formed a close working relationship with managing director Leslie Taylor. Hard-working and responsible, Morris would often be left in charge of the works when Mr Taylor was away in business, and his boss was so impressed that he had considered appointing him a partner.

Morris was working his usual Saturday morning shift on the day Christine went missing, and Mr Taylor recalled his right-hand man being his normal, unflappable self. Indeed, he said there was nothing out of the ordinary regarding Morris’ behaviour throughout the investigation, and he did not recall Morris ever saying anything that would suggest he had an interest in it.

“The whole of the Midlands was talking about it, I do not specifically remember if the subject did come up, but if there had been anything suspicious about his reaction, I would have noticed it,” Mr Taylor said.

Mr Taylor said he would chat daily with Morris, listening to stories about his hobby of photography and his plans to build a luxury bungalow in leafy Green Lane, Aldridge. The two men would socialise outside work, the last occasion being shortly after Christine’s murder. Accompanied by their wives, they would also attend business functions together.

Police cadet Alan Parker, who had helped in the search for Christine in August, 1967, had also unwittingly come across Morris weeks earlier when the killer was brought in for indecent exposure. Mr Parker, who was working in the collator’s office, went to log Morris’ details in the police files, and noticed that it was Morris’ second offence.

“Indecent exposure in those days was pretty rare, so two in a short time was unusual,” he said.

He brought the matter to the attention of his collator John Smith who passed the information on to Det Supt Ian Forbes, of Scotland Yard, who was leading the murder inquiry.

“I had never heard of Raymond Morris before although I suspect the murder team were already on to him.”

In January 1968, a team of 200 detectives renewed their house-to-house inquiries, seeking to visit more than 54,000 homes in Walsall borough. All men aged between 21 and 50 were given a questionnaire asking them to account for their whereabouts on the date of each abduction and murder, giving details of witnesses who could corroborate their whereabouts.

By the spring of 1968, detectives strongly believed that the killer was someone who had previously been questioned, but had been given an alibi by his wife. The records were re-examined, but by October, 1968 it looked like the trail was going cold.

But Morris was getting complacent. He changed his anonymous grey Austin Cambridge for a distinctive green-and-cream Ford Corsair, which he used to lure another girl into his car.

Ten-year-old Margaret Aulton had been building a bonfire on wasteland in Bridgeman Street, Walsall, when a man pulled up in his car, and asked Margaret if she would like to take some rockets and catherine wheels from the front passenger seat of his car. As Margaret approached the vehicle, she noted the passenger seat was covered in newspaper and that no fireworks were visible. As she began to hesitate, Morris attempted to drag her into the car, but Margaret broke free and ran off. The incident was witnessed by 18-year-old Wendy Lane, who noticed the kerfuffle as she left the chip shop across the road, causing Morris to speed away with his head lowered. Mrs Lane made a note of the vehicle, a green Ford Corsair with a cream roof, and the registration number, which she told police was 429 LOP. The police database drew a blank, but officers did notice that there was an identical Corsair with the number 492 LOP – and the registered keeper was Raymond Leslie Morris, of Green Lane, Walsall.

Morris was arrested the following morning. Officers seized his car, and drove Morris back to the police station in it. During the journey, one of the officers complimented him on the car, and Morris replied that he had bought it the year before, having previously owned a grey Austin Cambridge.

Morris was freed after Mrs Lane failed to pick him out of an identity parade, but the investigators who dealt with him were struck by Morris’ uncanny resemblance to the composite image. On their return to Cannock, they relayed their suspicions to their superiors, along with the fact that Morris had owned a car identical to the one used in Christine’s murder.

An examination of records revealed Morris had been questioned four times between 1964 and 1968 in relation to the abductions and murders, and had initially been considered a strong suspect. But on each occasion, his wife Carol had provided an alibi. No further action had been taken, although two police officers who had interviewed Morris during house-to-house inquiries in February 1968 had noted on his questionnaire: “Very good likeness to the Identikit; not satisfied with this man due to the unsatisfactory alibi of wife alone.”

The evidence against Morris was starting to mount. Car insurance records showed that Morris owned a two-tone Vauxhall Velox like the one used in the abduction of Julia Taylor, at the time she went missing. On day of Margaret Reynolds’ abduction in Aston, he had attended a business meeting in the area, driving a green company Hillman Super Minx. Finally, company records at Taylor Precision Instruments revealed he had clocked out of work at 1.13pm on August 19, 1967 – about an hour 15 minutes before Christine was abducted. On examining the evidence, Det Chief Insp Pat Molloy remarked: “I think we’ve found the bastard.”

Arrest

At 7.30am on November 15, Morris was stopped in his car as he drove to work. On being told he was under arrest in connection with the murder of Christine Darby, he replied: “Oh God! Is it my wife?”

Mr Molloy described making the arrest: “He sat in his car and hesitated, and I though he might make a break for it.

“Then he co-operated, which was just as well. We had made sure he wouldn’t get very far.”

He was taken to the station for questioning.

Carol Morris was also detained and taken to Hednesford police station, where she was interviewed by Scotland Yard detectives.

Initially she stood by her statement, that her husband had returned home from work at 2pm on the date of Christine’s abduction, before taking her shopping to Marks & Spencer in the afternoon.

Within a few hours, though, she retracted her story, admitting to given her husband a false alibi. She said on the date of the murder he did not return home until almost 5pm, saying he had been required to work late. He did take her to Marks & Spencer to pick up some cakes for her mother, but did not arrive until shortly before closing time.

Morris was said to be distraught when told of the news, but recovered his composure. He refused to take part in a second identity parade, but was successfully identified by Victor Whitehouse when police brought him into the station the following day.

Morris’s old Austin Cambridge was traced and subjected to forensic examination, while a search of Morris’s flat uncovered a small cache of homemade child pornography. The pictures had clearly been taken inside Morris’s flat, and the photographer was wearing a distinctive watch that had been found strapped to Morris’s ankle the previous day. The photographer’s hands were also visible in some of the pictures, showing several scars that matched those on Morris’s hands

Morris was charged Christine’s murder on November 17, 1968, and two further charges of indecent assault and the abduction of Margaret Aulton were also filed against him the following month. He appeared before Cannock magistrates on January 7, 1969, and went on trial the following month.

When he appeared before Stafford Assizes on February 10, 1969, Morris admitted the indecent assault charges, but pleaded not guilty to murder and attempted abduction. His defence counsel, Mr Kenneth Mynett, argued that the charges should be heard in separate trials to avoid prejudicing the outcome, but this was rejected by Mr Justice Ashworth, who said they should all be heard together.

Trial

Carol Morris gave evidence for the prosecution during the trial, saying she had agreed to corroborate her husband’s statements as she ‘didn’t think he could be the person responsible’.

Morris claimed in the dock that he had been beaten up by police who were investigating the case, and was never given the opportunity to appear in an identity parade.

On February 18, the jury took just two hours to convict Morris on both the murder and rape of Christine Darby, and the attempted abduction of Margaret Aulton.

On being sentenced to life imprisonment, Morris turned to the public gallery and glared coldly at his wife, before being led away to begin his sentence.

Judge Ashworth thanked Chief Supt Ian Forbes and his officers for their work in bringing Morris to justice.

“There must be many mothers in Walsall and the area whose hearts will beat more lightly as a result of this verdict,” he said.

“It must have been a nightmare for mothers and father in Walsall over the last months, when they heard, maybe of a child missing.”

Not everybody was satisfied that justice had been done, though. Neville Murphy, from the Bradley area of Bilston, launched a petition calling for the return of capital punishment in the wake of Christine’s murder. By the time of Morris’s conviction, more than 18,000 people had signed in support of it, and Mr Murphy said he would be seeking a meeting with former government minister Duncan Sandys who said he would be tabling a Private Members’ Bill to restore the death penalty.

Morris was taken to HM Prison in Durham, where he would join Moors murderer Brady. Morris unsuccessfully appealed against his conviction the following November.

He was later transferred to HMP Preston, where he again served alongside Brady. He would remain their until his death on March 11, 2014, at the age of 84.

Morris protested his innocence right up until his death. The Criminal Cases Review Commission denied him a further appeal, but in November 2010 he was granted a judicial review, but again his case was rejected, and the following year he said he intended taking his case to the European Court of Human Rights.