Black Country Zeppelin raids: Remembering the terror from the skies 100 years on

As families settled in their homes for the evening they could have had no idea of the terror that loomed large in the skies above the Black Country.

Above them, lost in fog, two huge German Zeppelin bombers hung – the crews ready to attack.

The pilots guessed they were over their intended target, Merseyside, but they were actually 90 miles south, over Tipton, Wednesbury, Bilston and Walsall.

The bombs were dropped and 35 lives were lost as homes and businesses were destroyed. The date was January 31, 1916.

It remains the most devastating atrocity to hit the Black Country.

Details surrounding the Zeppelin raids were scant in the immediate aftermath of the bombings, as the Express & Star's coverage at the time showed.

News of the bombings was included in the next day's edition on February 1, 1916, but at that stage 'no considerable damage' had been reported. There was no Twitter for reporters to rely on in those days, instead relaying that a message had come through to the Express & Star offices from the War Office.

More clarity came in the next day's edition when it was reported that people had been killed in Midlands counties including Staffordshire, which at that time included Walsall, Tipton and Wednesbury. On February 3, the carnage became more apparent when we reported how the German bombers were 'quite unable to ascertain their position' and that 14 houses were destroyed and a church badly damaged under the headline 'Wanton slaughter of women and children'. An advertising opportunity was clearly seen, with readers being offered the chance to 'insure against Zeppelins at low Government rates'.

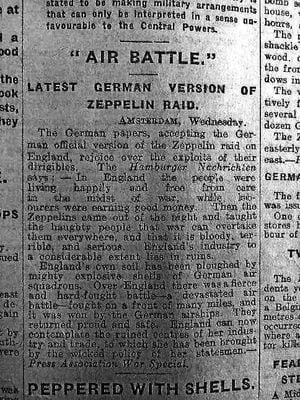

The view from Germany was also carried by the Express & Star, in which an article from the Hamburger Nachrichten claimed the Zeppelins 'taught the haughty people that war can overtake them everywhere and that it is bloody, terrible and serious'.

It also said 'England's industry to a considerable extent lies in ruins'. The Express & Star reported on the tragedy at the time, with a doctor one of the first witnesses to talk about a victim who had suffered devastating wounds as a result of the missile hitting her.

Although Britain was a country at war and had been for almost two years, air raids were not something that played on people's minds as they had hardly ever happened before – there was no air sirens and shelters that became associated with Second World War Britain.

That blissful unawareness was particularly the case in the Black Country, with the Germans having focused most of their attention on London and the east of England up to the point.

Historian Ian Bott, from Wednesbury, who has written a book on the raids called the Midlands Zeppelin Outrage, said there was an air of complacency even among local government officials.

He said: "There were no contingency plans.

"Birmingham had wisely for some months prior taken to the practice of blacking out so they couldn't be seen from above.

"There was a culture of complacency. It had been mooted in newspapers a few weeks before the idea that the Zeppelins could find us but it was laughed off. It was thought it would be dangerous to traffic if we blacked out."

So, although they weren't sure exactly where they were, the bright lights below made it clear to the airship pilots they were over a populated urban area.

Nine airships had set off from the north west coast of Germany. The L.21 and another Zeppelin, L.19, hit the Black Country at 8pm and midnight respectively.

Kapitanleutnant Max Dietrich, who commanded the L.21, which, at 585ft long and 61ft wide, was the pride of the German fleet, believed he was over the Irish Sea and saw the lights of two towns separated by a river. He thought they they were Liverpool and Birkenhead. In fact it was the Black Country and the 'river' was one of the many canals that wind through the region.

Mr Bott said: "January 31 was a moonless night. It wasn't randomly chosen, it was so they couldn't be seen. They encountered thick fog when they arrived and they became hopelessly scattered and disorientated. Only two of the nine made it to the Black Country. The Zeppelins were deliberately instructed to target civilians to try and break their morale."

And when Dietrich took aim, there was nothing those below could do but hope they would not be caught in the line of fire.

The first bombs fell on Tipton at 8pm. Three bombs dropped on Waterloo Street and Union Street, followed by three more on Bloomfield Road and Barnfield Road. Two houses were destroyed in Union Street and others were damaged. A gas main was set alight.

Five men, five women and four children died.

L.21 floated to Lower Bradley, unleashing another five bombs and killed Maud and William Fellows. By 8.15pm it was over Wednesbury and killed more than a dozen more. Other bombs fell at the back of the Crown and Cushion Inn in High Bullen and on Brunswick Park Road.

"We heard this noise in the sky and we all looked up," recalls one survivor of the deadly bombings.

"There was this huge object.

"It seemed only a few hundred feet up.

"I could clearly see two men in a basket container underneath.

"They were dropping things out over the side.

"Of course, we hadn't a clue what they were."

Len Turner paints a terrifying picture of what it was like for those who lived through the Zeppelin raids – the bewilderment, the curiosity and the fear.

These people had come to bomb them as they rested in their homes.

Although air raids would become associated with Second World War Britain, they were not something people were accustomed to two decades earlier.

But it soon became clear to those below that they were under attack from the massive airship that loomed ominously overhead.

Len, from Lower Penn, was just six years old when the bombs dropped.

He died in 2009, aged 98, but five years earlier had spoken to the Express & Star about the bombings.

Len, who owned and ran the Express Cafe in Lichfield Street, Bilston, with his wife Thora from 1936 to 1958, said: "We ran for a cellar.

"I remember two things just like it was yesterday.

"There was this old lady in the street, terrified, hysterical, pulling her dress up to cover her face.

"Inside the cellar there were candles lit and I saw this real thug from our street, a man who was always beating his wife.

"Well, he was on his knees praying out loud."

Like many families, the terrified Turners had no father to protect them.

Charles Turner, an insurance agent, had volunteered at the start of the war and was away in France.

"I remember when he went, my mother cried a bit," Len said.

"But she always tried to hide her face from us. She was a very brave and wonderful woman."

At the best part of two football pitches long, the Zeppelin remains the largest combat aircraft ever to have flown and was a fearsome adversary. It was akin to a person hurling stones at scurrying ants, such was the disadvantage in size and muscle power.

Mr Bott said: "I feel their hopelessness when looking at what happened. Most people in the Black Country had never seen any form of aircraft in the sky and along comes this huge craft that is 200 metres long suddenly raining down explosives on them. There was nowhere to run and nowhere to hide."

As the dust began to settle from the first wave of bombings, in came the L.19. Though its bombs caused considerable damaged, nobody is thought to have been killed in its attack on Wednesbury, Dudley, Tipton and Walsall.

The Bush Inn in Tipton was left a ruin after a bomb hit the roof of a nearby house in Park Lane West, bounced onto the road and exploded in front of the pub.

More damage was caused in Walsall where bombs fell on a stable in Pleck Killing a horse, four pigs and about a hundred fowl. More bombs fell in Birchills, damaging St Andrews Church and vicarage in Hollyhedge Lane.

A century on from the bombings, services have been organised across the Black Country to honour those who lost their lives.

Plaques containing the names of some victims are also being unveiled. Many of the dead were not afforded a grand send off and some ended up in unmarked graves.

A plaque is to be placed in Wood Green Cemetery in Wednesbury featuring the names of the 13 people who died in an area known as Hellfire Corner. They include Ina Smith and Mary Evans, who were aged just seven and five when they died. Several surnames appear more than once, suggesting members of the same family died in the attack. These include Betsy and Edward Shilton, and Joseph and Thomas Horton Smith.

A plaque will also be unveiled in Tipton during a ceremony at the premises of H C Pullinger in Union Street on January 31, close to where the bombs fell exactly 100 years earlier.

Wednesbury councillor Peter Hughes said: "To a degree many of the names have got lost and this is an attempt to try and bring them back. There were so many people who died as a result of being in combat but these were innocent civilians that were killed. It is part of Wednesbury's history and it is important to make sure the names are commemorated."

To many people familiar with Black Country towns such as Tipton and Wednesbury, the road names will roll off the tongue – they may become stuck on them every day on the commute to work, but what they might not know is the tragedy that unfolded 100 years ago, that homes were reduced to rubble and lives changed forever.

It is likely there are people living where the bombs dropped today who know little or nothing about what happened and Mr Bott believes it is important the victims are remembered.

He said: "It's something I feel very strongly about – 100 years later we all should be remembering them and wanting to know more about it. I personally feel with the 1914-18 war, there will be commemorations in 2018 to mark 100 years but after that it will be forgotten. This is why I felt it was the right time to research it and present it to the public.

"These people died horrible deaths. It is certainly the worst atrocity in the Black Country in terms of ordinary everyday people losing their lives."

As for the Zeppelins that caused so much carnage that day, they did not get to fly for much longer.

The L.21 was shot down in November of the same year while on another mission while the L.19 never even made it home. While heading back, Dutch sentries fired and hit the Zeppelin repeatedly. The rifle fire punctured the hydrogen gas cells and the airship plunged into the North Sea.