Matt Maher: Aston Villa and West Brom hero Garry Thompson finds it’s good to talk

Garry Thompson would be the first to admit he’s never minded the sound of his own voice.

During a 20-year playing career which featured nearly 600 appearances and memorable spells at Coventry, Albion and Villa, it often got him into trouble.

“At this club, all I ever hear is you,” Graham Taylor once told his striker early in Villa’s promotion-winning 1987-88 season.

Yet just recently talking has never been more valuable to Thompson. The death of his parents within months of each other in 2018 hit him hard and after consulting his wife and family he decided to undergo counselling.

“If you had met me at the time, whether it be at a ground before a match, or anywhere, you would never have noticed any difference,” he says.

“But inside I was breaking. I would wake up in the morning and feel like someone was standing on my chest. That was anxiety.

“I effectively got tricked into the counselling by wife and son and for the first couple of sessions I wondered what I was doing there.

“But it has been brilliant. It has made realise I can express my feelings and don’t need to be the class clown. Before then I was bottling things up and at some point there was going to be an explosion. At some point it could have killed me, I guess. Now I’m no longer afraid to show my feelings.”

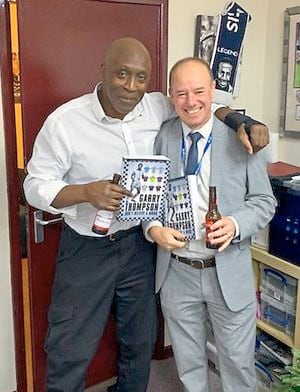

The revelation, which arrives late in Don’t Believe a Word, his autobiography released this month, will surprise many for whom Thompson, these days a popular pundit on local radio, has always been a man with whom a smile and a joke are never far away.

There are plenty of laughs in his book. There are no shortage of tears too. More than anything, his story is full of heart with his parents, Eulalie and Charles, maintaining a constant presence.

“When I needed inspiration, Mom and Dad were there,” writes Thompson. “When I needed hope, Mom and Dad were there and when I needed love, they were there to wrap me in a blanket of warmth, tenderness and affection.

“They gave me the spark, the belief and the confidence to make something of my life.”

One of five children who grew up in the south Birmingham suburb of Kings Heath, Thompson played for nine clubs during his career but to describe him as a journeyman would be a significant disservice

Capped by England at under-21 level and during his time with Albion was on the fringes of the senior team, though the call-up he craved never came.

It was with the Baggies that Thompson was at his peak, scoring 20 goals in the 1984-85 season and being named the club’s player of the year.

It was at The Hawthorns he got to play alongside Cyrille Regis, whose achievements had been an inspiration to Thompson and a generation of other young black players.

Yet Thompson was also a trailblazer himself, having become Coventry’s first black player in two decades when he made his debut as a 17-year-old in 1977.

“Mom always told me I would need to work twice as hard to get half as far because of the colour of my skin,” says Thompson.

“But I was never going to let people knock me off my stride because they didn’t like me being black.

“You couldn’t let the racism knock you down because at the end of the day the only person you were beating was yourself.

“I had a wife and kid to support, my brother and my mom. I was looking after my family. If I allow people to break me or push me back, they suffered.

“When fans used to shout racist things at me, send me hate mail, it didn’t bother me.”

As team-mates, Regis would act as a mentor to the younger, more aggressive Thompson. Only once, to his knowledge, did the man he affectionately refers to as “Big C” lose his cool. That came before the second leg of a League Cup tie with Millwall in October, 1983.

“C had just parked up and was walking to the ground when he overheard two Millwall fans abusing a young black girl,” says Thompson.

“He told them to calm down and they started abusing him. The next thing you know he has sparked both of them out. It was like something from a superhero movie!”

Albion, trailing 3-0 from the first leg, promptly won the match 5-1 with Regis and Thompson both scoring twice.

“He was incredible that night,” recalls Thompson with a sigh. “That match was a pleasure to play in.”

Thompson never wanted to leave The Hawthorns in 1985 but the decision was effectively taken out of his hands when a big money move to Swiss champions Servette broke down and the Baggies, having already signed Garth Crooks and Imre Varadi, needed to cash in.

It proved a bad deal for both parties as 12 months later Albion were relegated while Thompson, after a season with Sheffield Wednesday, arrived at Villa.

On the surface it looked a dream move. Thompson had been a Villa supporter from a young age. His dad remained a huge fan.

“Doug Ellis always used to say it was the quickest deal he ever did,” says Thompson. “He offered me £600-a-week, a £25,000 signing on fee and a Montego and it was done.

“But it quickly became apparent I had joined the right club at the wrong time.

“The team floundered. I was the local boy who had come home and all of a sudden I was surrounded by a sea of s***.”

As Villa spiralled toward relegation in 1987, Thompson struggled with a mystery injury which at one stage even saw chairman Ellis offer him money to retire.

“He offered me either £20,000 or £25,000, I can’t remember which exactly, to cancel my contract,” says Thompson.

“But I was never going to do that. For one thing, I could earn more money by just sitting out the remaining years of my deal but most importantly I would never, ever, have let things end like that. The club had been relegated and we had to put things right.”

After surgery on an injury eventually diagnosed as an inguinal ring hernia, Thompson returned in November 1987 and began helping Villa push toward an instant return to the top flight. His 11 league goals included a memorable double in a 2-1 derby win at St Andrew’s, with Villa eventually securing promotion after a nervy final day 0-0 draw at Swindon.

The picture of a shirtless Thompson being carried off the County Ground pitch by jubilant supporters remains iconic yet behind the scenes relations between the striker manager Taylor were fractious.

“We were celebrating in the dressing room and Graham was just watching us,” he says. “I remember saying to Alan McInally: ‘He’s working out who to get rid of and who to keep’.”

Thompson would be one of those out the door later in the year, moving to Watford.

“It took years before me and Graham made our peace,” says Thompson. “One day he explained to me that after my injury I’d become a Second Division striker.

“He told me I would never have accepted being a fringe player in the First Division and that is why he moved me on. Of course, I wish he’d told me at the time. But looking back, I understood.”

Thompson, who went on to play for Crystal Palace, QPR, Cardiff and Northampton before brief stints in management with Bristol Rovers and Brentford, looks back on his career with few regrets.

Now 61 and a grandfather-of-four, he no longer experiences the “explosions” of temper he admits sometimes held him back.

“There were times I would just blow up,” he recalls. “I remember playing for Coventry against Brighton and Steve Foster, who I knew well, wound me up so much I punched him. The ref missed it but Ron Greenwood, the England manager, was in the stands and didn’t.

“There was always a danger my mouth would run away with me or I would be overly aggressive in certain situations.

“I loved playing the game. Yes, I think I should have done better but I think every player probably feels that way. Your career is gone in a flash.

“I’d much prefer to be remembered as an OK guy. Forget the football. If people look at me and think ‘yeah, Thommo, he’s a good bloke’ then that is good for me.”

Don’t Believe a Word, written by Garry Thompson and Bill Howell, is out now and available to buy at curtis-sport.com