First World War soldier's letters tells of life on the frontline

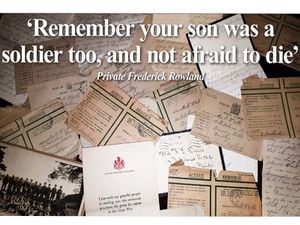

Poignant letters from a First World War solider to his sister in the Black Country paint a humbling picture of his hopes, pride and humour before he was killed in action aged 20 just weeks before the Armistice.

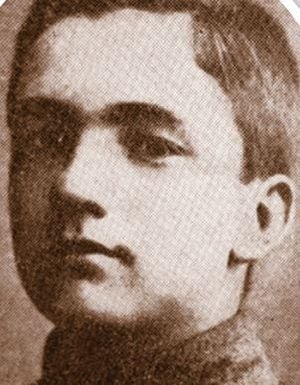

Private Frederick Rowland had been in frequent touch with his family and the close bond with his sister shone through in letters between the frontline and her home in Dudley.

He was awarded the Military Medal for gallantry and devotion to duty but in typical modest style mentioned it as an almost throwaway comment in a letter which begins by describing the abundance of fruit on sale in an Italian market.

“It was market day here the day before yesterday. The place was packed. We can get fruit galore here; peaches, cherries, oranges and goodness knows what. We had our first lot of new potatoes for dinner yesterday and they went down a treat. I suppose you have had plenty by now. Dear Katie you will be pleased to know that I have won the Military Medal.

“They gave me the ribbon last Sunday. We don’t get the medal itself until we get back to England. There were two of us got it in our platoon. We have been congratulated by the officers in our company. I wrote to mother yesterday and told her.

“There are plenty of kidney beans, peas, young potatoes and tomatoes in the shops here. I am enclosing some views of Venice. That is not where we are now though. I will send some more later on.”

He later wrote to ask his sister to send a piece of ribbon – giving precise measurements needed to pin the medal to his chest when he returns. “I shan’t have to go to see the King for my medal. I shall get it when I get to England again. It’s only V C (Victoria Cross) they have off the king and officers’ medals.

“It will tell you what I had it for in the (news)paper.

“I should be glad if you could send me some ribbon. It soon gets dirty out here. I think it is three pence an inch. If you send me two inches that will be plenty. I have got a piece that the captain gave me, beside the bit that I wear on my tunic but I want to send that home to dad for a keepsake. You won’t mind me not sending it to you, will you? I know dad will like to have it. I have some little souvenirs for you when I get home.”

As a post script he adds with pride; “I shall be able to stick out my chest when I get home.”

Frederick joined the army in February 1915 and went out to France in May 1916 when he was wounded in the arm and sent home to recuperate at the military hospital in Lewisham.

In one of the letters written in pencil and signed from “your loving brother Fred” he wrote; “We landed at Dover and then came straight across by hospital train.

“We didn’t half get a reception here, I can tell you. I suppose the people had got to know there was a convoy of wounded coming in. Anyway, there were crowds of people at the station. As we went by in the motors, they cheered and threw flowers – roses and white heather - and packets of cigarettes and papers at us.

“The car was full of flowers. Gosh, we were like some blooming lords riding through the people. They did make a fuss of us.

“This is a good hospital. We get splendid grub. It’s a treat to have some good food and pudding and eggs. Different to the living over in France.

“This evening a lady bought us some grapes, plums and chocolate.

“The doctor said my arm was going on fine this morning.

“It’s pretty lively here. The hospital is in the main road. There are tram cars going by all day long.

“We get a packet of cigarettes every other day, whatever sort we like, and some sweets and writing paper and envelopes.

“When the wound gets better, we get 10 days leave and a sovereign so it’s not so bad.”

Fred also served in Italy where he won his Military Medal in 1917 for bravery as one of the first to enter enemy trenches.

He wrote that The Alps reminded him of being with his sister on the hills at Malvern. “Only these are a bit higher,” he joked.

Fred’s sister Kate Wells, of Kitchener Road, Brewery Fields, Dudley, remained in frequent contact by letter, relaying news of everyday events at home to keep his spirits up.

She told him that the family had acquired a pet dog Jack, nicknamed Snatcher by her father – also named Fred. The dog was proving a handful, growling at anyone who approached the house and chewing her best shoes.

Children had also stolen carrots from the family’s vegetable patch, causing Kate’s father to “turn the air blue.”

But on October 29, 1918, came news the family had been dreading.

Kate received a letter from her mother to say Fred was among the missing.

“You must be prepared for the worst news. You must try and be brave but it must seem hard. I felt that we should never see him again,” the letter said. Their fears were confirmed when official news came from the War Office that Fred had been killed in action in France on October 5.

His parents, of Worcester, received a letter of sympathy from his officer, saying he was one of the bravest men in his platoon and that he died bravely, nobly doing his duty as he had always done. The letters and other mementoes came to light when Fred’s great niece Eileen Wells, of Stourbridge, was helping clear possessions from a relative’s home.

She said: “I was moved to tears when I read the letters. It really brings history to life and makes you realise that every one of the soldiers who gave their lives were ordinary men with an extraordinary story and a life with family and friends who loved and missed them. Fred’s story echoed that of thousands who represented values of a different age.”

A tribute from Fred’s parents read; “We longed for his safe returning; And longed for a clasp of his hand; But God has postponed the greeting ;Till we meet in a better land.”

Fred was buried at Beaurevoir British Cemetery, 2.5 miles East of Le Catelet, Aisne, France.

His sister Kate and her husband Fred went on to spend most of their life at Warrens Hall Road, Sledmere Estate, Dudley.

A letter Private Rowland had left for his mother in the event of his death, said: “You loved me all your life mother, And fondly I loved you.

“I will meet you at The Golden Gates and all my comrades too.

“I have died for the dear homeland, For the brave and the free. Always remember that when you think of me.

“Now the sad war is over and the boys come marching home, you will think of your fallen hero who will never more return. Just look upon them, Mother, though tears may dim your eyes, remember your son was a soldier too and not afraid to die.”

By Eileen Wells