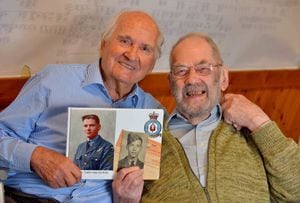

Wartime memories as RAF brothers reunited in home village

Two brothers, now in their 90s, met up in their childhood village in Shropshire for an annual reunion.

Roy Tomlin, 98, and Ron, 96, recalled their wartime expoilts during the get-together at Ford Parish Hall near Shrewsbury.

Ron, who now lives in Streetly, Walsall, and Roy, who moved to Abergavenny, were joined by 38 family members for the party.

The younger one played a crucial role in the bombing of Germany during the Second World War, the older one was instrumental in the early use of radar.

Ron was a 19-year-old bomb-aimer in the 10 Squadron RAF when he was called to take part in raids over the cities of Hamburg and Nuremberg in August, 1943.

The first two raids over Hamburg went fairly smoothly, but on third the plane developed an engine problem, which the crew reported on their return to its base in Halifax.

“We assumed our bomber was US (useless), and went to bed down at 4am,” he says.

“But we were woken up and told there was nothing wrong with the plane, and we were going to Nuremberg, so we were on operations two nights in a row.”

The journey to Nuremberg took eight hours, and on the return journey during the early hours of August 11, the engine problem recurred. A second engine on the opposite side of the plane also developed a fault.

The plane lost height as it flew over Dieppe, descending to 9,500ft, making it a sitting duck for the enemy. Gunfire duly arrived as it descended over the English Channel, damaging the inflatable lifeboat. The crew were forced to make an emergency landing on water, and patch the dinghy as best as they could.

“When we ran out of patches, we had to put our fingers in the holes, we were pumping all the time to keep the boat inflated,” says Ron.

“We were in the sea for about 17 hours, before the Germans caught us.

“We had swallowed a lot of oil, and had been vomiting all the time. I don’t know how the other crew members were feeling, but I was quite glad to be rescued by a German boat.

“Had we not been captured, we would have probably ended up in the North Sea, which is much more difficult to be rescued from.”

Four days after their capture, they were sent to the Gestapo headquarters at Dulag Luft for interrogation.

It was something Ron had been prepared for by his RAF training.

“We had been told what to expect, they would move you from hut to hut,” he says.

“Some nights they would put you in the same hut as one of your crew, another they would put you in with a stranger.

“The important thing was you never talked about anything, because if you were talking to your crew mates, somebody might have been listening, and if you were with a stranger they might already be collaborators.

“It wasn’t pleasant, but apart from them sometimes waving guns about, there was never any violence from them.”

He was then transferred to Poland, finishing up at the Stalag Luft IV camp until the Russian advance of February, 1945. As the Russians moved closers, the prisoners were ordered to march 500 miles on foot back to Germany, often being expected to complete 30 miles a day.

On reaching Fallingbostel in Saxony, Ron and his pilot refused to march any further until he had his injured foot operated on, and they stayed put.

“Most of my crew went with them, but Dibben, the pilot and I, went into sick bay, lay on the floor and said we were too sick to move, and we just stayed there,” he says.

Ron’s German captors made little effort to coerce them, and simply left them behind, and they were liberated two days later on April 16, 1945, by the advancing British forces.

“We knew the Army was getting close because we could see the searchlights in the sky,” he says.

He says on the whole, the men were treated fairly by the Germans.

“They were just doing their job,” he says.

“They would rush you a little bit sometimes, but if you did as you were told they were generally alright.”

After being liberated in April, 1945, Ron returned home where he was treated at the RAF Cosford hospital for dysentery, returning to his mother’s house in Birmingham by VE Day. He trained as draughtsman, and married his wife Freda in 1954.

Older brother Roy joined the RAF in 1941 as a radio mechanic, and quickly became involved in the development of radar.

“Most people know radar was used in the Battle of Britain in a defensive capacity, but not so many people know that it was also used offensively, to guide the bombs,” he says.

Roy says the idea of using radar as a navigational aid was first suggested in 1939, but was initially shelved because defensive radar was at that time much more important.

However, by 1942 the situation had changed dramatically and there was a clear need to improve navigation.

“By the beginning of 1943 more accurate navigational aids were needed to assist bombers to find and bomb targets in adverse conditions,” he says, adding that a new system was developed to serve this purpose.

Roy was posted to Fairlight, near Hastings, in the autumn of 1943, and after the system had been proved and adopted by both the RAF and the American Air Forces a further station was set up.

He remembers being a senior mechanic on duty for the night watch June 5, 1944, completely unaware of the preparations being made for the invasion of Normandy.

“When we arrived at the site we learned from the off-going watch that while they had been operational earlier in the evening nothing was planned for the night,” he says.

“We were therefore amazed to receive a signal at about 11.15pm telling us of an operation to last from 11.45pm until 5am, with a target given in the middle of the channel off Boulogne.”

He says normal procedure was that crews should inform their commanding officer or NCO if they received strange operational orders. However, on this occasion Roy and his senior operator decided it was not necessary, believing it must have been a training exercise.

“About 1am the commanding officer arrived, he had been out in Hastings and was cycling home to his billet at Fairlight and said he had heard aircraft ‘stooging around’ and wondered if we knew what was happening,” says Roy.

“He stayed about half an hour then went home. Just before it got light next morning the guns on the enemy coast opened up, and when day dawned we were surprised to see a fleet of tugs hauling peculiar shapes down the channel.”

It later emerged they had unknowingly been involved in Operation Glimmer, a highly sophisticated form of subterfuge, to draw German troops towards Boulogne, away from the beaches of Normandy.

He says: “We learned later that day that we had provided the navigation for Operation Glimmer, eight aircraft of 218 Squadron flying a mile apart for a set period of a few minutes towards the French coast, then turning back for another, shorter, period, then reversing direction again, dropping a special form of ‘window’, the whole operation giving the impression of an invasion fleet sailing at about seven knots towards Boulogne.”

In November that year, Roy went over to France along with the Americans. After leaving the RAF in 1946, he went to work for Electricar in Birmingham, later moving to Derbyshire, and before eventually settling in south Wales. He has two daughters, Ann and Sue, four grandchildren, and eight great-grandchildren.