Fossil of dead-end branch of life which became extinct to go on display

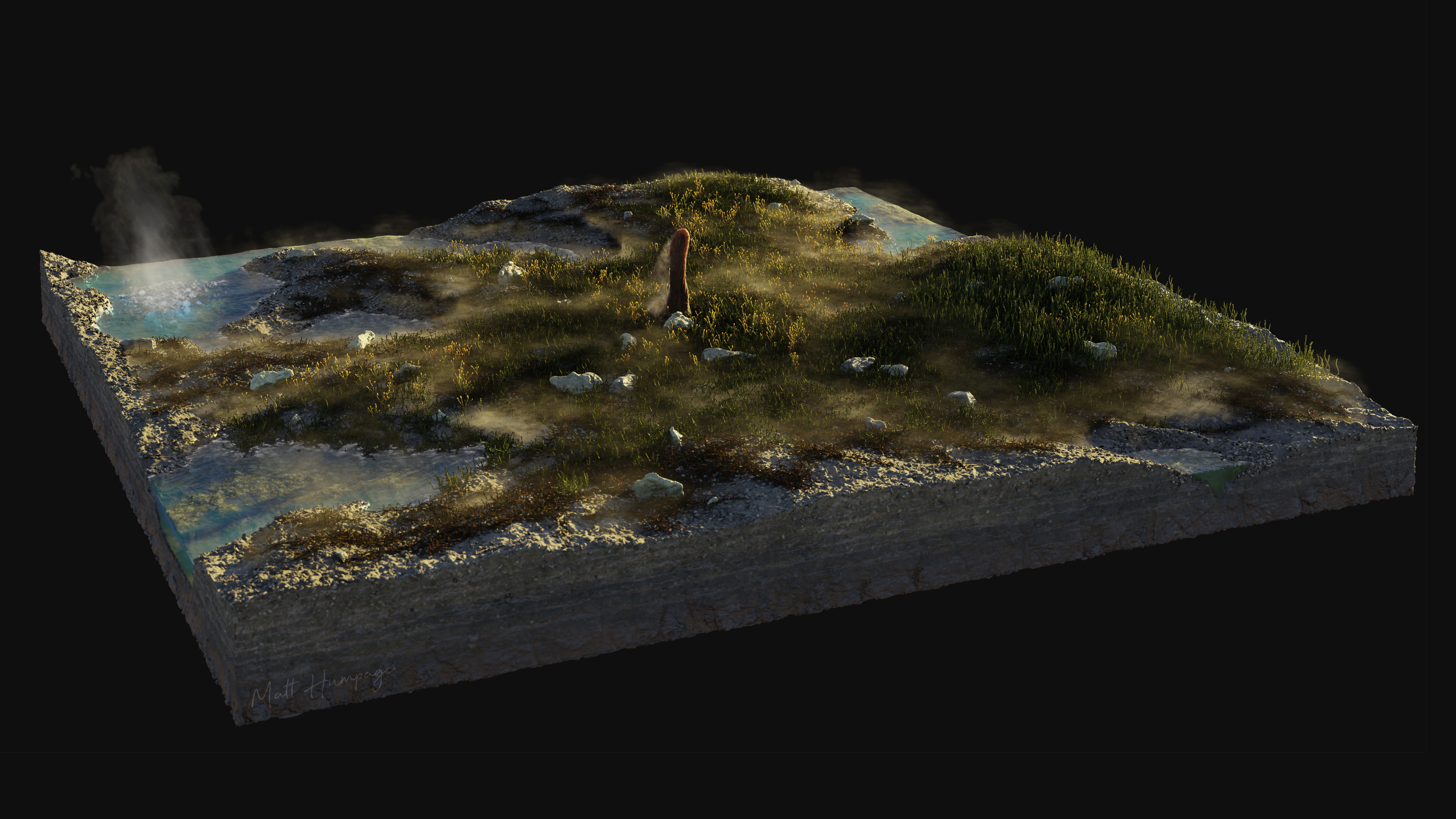

The prototaxites fossil, which is about 410 million years old, was found near the village of Rhynie in Aberdeenshire.

A fossil from a lifeform which once towered over the ancient landscape is to go on display at the National Museum of Scotland.

Prototaxites, which grew to more than eight metres tall, belonged to an “entirely extinct evolutionary branch of life”, scientists believe.

Experts once thought prototaxites, which became extinct about 360 million years ago, were a form of fungus but some experts now say they were neither fungi nor plants.

The fossil, which is about 410 million years old, was found in the Rhynie chert, a sedimentary deposit near Rhynie, Aberdeenshire.

It has been added to the collections of National Museums Scotland in Edinburgh.

In a new paper, published in Science Advances, researchers said the fossilised sample backs up the theory that prototaxites were an entirely different form of life no longer found on Earth.

Dr Sandy Hetherington, co-lead author and research associate at National Museums Scotland, and senior lecturer in biological sciences at the University of Edinburgh, said: “It’s really exciting to make a major step forward in the debate over prototaxites, which has been going on for around 165 years.

“They are life, but not as we now know it, displaying anatomical and chemical characteristics distinct from fungal or plant life, and therefore belonging to an entirely extinct evolutionary branch of life.

“Even from a site as loaded with palaeontological significance as Rhynie, these are remarkable specimens and it’s great to add them to the national collection in the wake of this exciting research.”

Co-lead and first author, Dr Corentin Loron, from the UK centre for Astrobiology at the university, said: “The Rhynie chert is incredible. It is one of the world’s oldest, fossilised, terrestrial ecosystems and because of the quality of preservation and the diversity of its organisms, we can pioneer novel approaches such as machine learning on fossil molecular data.

“There is a lot of other material from the Rhynie chert already in museum collections for comparative studies, which can add important context to scientific results.”

Co-first author Laura Cooper, a PhD student from the Institute of molecular plant sciences at the university, said: “Our study, combining analysing the chemistry and anatomy of this fossil, demonstrates that prototaxites cannot be placed within the fungal group.

“As previous researchers have excluded prototaxites from other groups of large complex life, we concluded that prototaxites belonged to a separate and now entirely extinct lineage of complex life.

“Prototaxites, therefore, represents an independent experiment that life made in building large, complex organisms, which we can only know about through exceptionally preserved fossils.”

Dr Nick Fraser, keeper of natural sciences at National Museums Scotland, said: “We’re delighted to add these new specimens to our ever-growing natural science collections which document Scotland’s extraordinary place in the story of our natural world over billions of years to the present day.

“This study shows the value of museum collections in cutting-edge research as specimens collected over time are, cared for and made available for study for direct comparison or through the use of new technologies.”