Carrying the hopes and good wishes of Wolverhampton and the Black Country, Princess Xenia took off on an epic flight which promised to carve a place in aviation history.

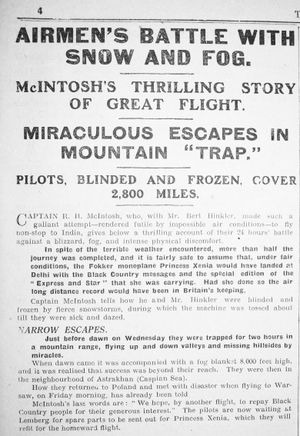

How bad weather defeated "All-Weather Mac" on an aviation record attempt which would have brought glory to the Black Country.

This was back in the 1920s when intrepid aviators, both men and women, risked their lives to connect the world - and in this case link up the British Empire.

The aircraft Princess Xenia was carrying something else - copies of a specially printed edition of the Express & Star conveying greetings to the people of India, the intended destination after a record-breaking non-stop flight.

It never made it. The blue and yellow Fokker monoplane hit bad weather which was too much even for pilot Captain Robert McIntosh, whose reputation for flying through the worst conditions had led to him being nicknamed "All-Weather Mac" (or, as the E&S would have it, "Dirty Weather Mac.")

The plane landed in Poland, but the good news was that both McIntosh and fellow pilot Bert Hinkler were unscathed, unlike so many other aviation pioneers of that era who perished in accidents or simply disappeared.

Why were the people of the West Midlands so invested in this particular flight? It was sponsored by the Express & Star, the proprietors of which were enthusiastic supporters of air travel and civil aviation generally.

In an aerial salute before the pair set off on their adventure, they flew low over Wolverhampton - circling St Peter's Church and the town hall, and sailing over the Express & Star offices in Queen Street - Walsall, Willenhall, Wednesbury, and surrounding districts, bringing some traffic to a halt as eyes gazed skywards, before heading south to Upavon airfield in Wiltshire, their starting point.

Loaded with 750 gallons of fuel, Princess Xenia took off on the afternoon of Tuesday, November 15, 1927, watched by a clutch of spectators, who held their breath as the heavily laden machine clawed its way into the air.

It was carrying letters from Lord Dartmouth, the Mayor of Wolverhampton, and several local organisations, together with the copies of the latest edition of the Express & Star containing a special Empire Air Supplement. Had things turned out differently it would have been the first British newspaper to arrive in India by air.

Mrs Hinkler had also prepared food and drink for their journey - sandwiches, fruit, chocolate, meat, lozenges, hot coffee, tea and cold water - which were supplemented by a contribution from the officers' mess at RAF Upavon.

Before departing Captain McIntosh told our "Aeronautical Correspondent," in what some must surely have wondered might be his last recorded words: "We haven't forgotten Wolverhampton, and you can be sure that if we win through you will see us there again. Please remember me to all the friends I made on my visit there."

The pilots carried with them mascots from Wolverhampton admirers. They would indeed need good luck, as everybody was acutely aware of the risks they were running in an era in which there were multiple hazards, of which encountering bad weather in mountainous terrain was one of the most lethal.

And that was what happened. Over Europe McIntosh and Hinkler found themselves blinded and frozen by fierce snowstorms, and just before dawn on the Wednesday were trapped for two hours in a mountain range, flying up and down valleys and missing hillsides by miracles.

Daylight revealed them to be in a fog blanket 8,000 feet high, and somewhere in the region of Astrakhan they realised success was beyond their reach. Not wanting to land in Russia, and having completed around 2,800 miles of their 4,000 mile journey, they decided to turn back, coming down in a ploughed field in Poland.

With Princess Xenia being overdue in India with nothing being heard, concern grew. The New York Times noted grimly that the route took the plane over territories inhabited only by "savage tribes." In fact, after spending a night in a Polish police station, the pair took off again intending to get to Warsaw.

"But it was not to be," McIntosh later told the E&S.

"A snowstorm compelled us to descend, and we had almost come to rest when our undercarriage suddenly collapsed, and the propeller was snapped. A wing-tip also crumpled up. Two peasants were slightly injured."

Princess Xenia, a Fokker F. VIIa which had been named after a Russian princess, would be repaired and, under new ownership and a new name - The Spider - make further epic flights, including breaking the record from London to Cape Town and back. The aircraft was scrapped in 1937.

Hinkler, who was Australian, took off from England in January 1933 in an attempt to set a new record flying to Australia. Nothing more was heard from him until his wrecked plane, with his body nearby, was found months later on an Italian mountainside.

In contrast McIntosh lived a long life devoted to aviation, and would be honoured by Eamonn Andrews on the TV show This is Your Life. He died in 1983.