D-Day special report: June 6, 3.30am to 7.30am, the Beach Landings

Long before the Allied armada hit the Normandy beaches, midget submarines were only a few yards offshore, watching from the shallows.

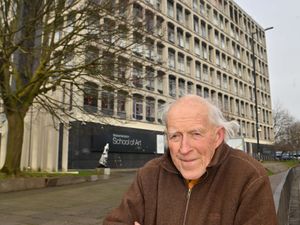

Some 'sneaky-beaky' units were silently creeping ashore. Jack Palmer, from Netherton, was one of the first. His tiny Royal Signals detachment was landed at dead of night to provide radio systems for the invading army: "By 3.30am on June 6 we pulled into shallow water on the Normandy coast," he said.

"We disembarked in a hurry. The skipper seemed rather anxious to be away. Pulling the cable carrier up the beach proved to be a hell of a job. In the dark, a number of steel tripods had to be circumvented. Unknown to us they were heavily mined. Fortunately there were no mishaps. It was quiet as the grave with not a soul anywhere, least of all German troops. We led the invasion on D-Day."

Stan Twyman, of Codsall, was a boy in arms, an 18-year-old midshipman on an armoured tank-landing craft, LCT (A) 2238.

In the grey, squally morning of D-Day, he gave the most momentous order of his life.

On the approach to Gold Beach some landing craft struck submerged mines and blew up. Others were holed and vanished in seconds. But his made a text-book run-in to the beach.

"Ramp down!" shouted the teenager, securing his place in history.

The steel ramp fell forward. His cargo, a flail tank designed to carve paths through minefields, moved steadily down the ramp. The landing craft next to his was stranded on the beach, unable to withdraw. Another landing craft nearby was shattered by an enemy shell.

"We were lucky," he said. "It was a very quiet section of the beach. But none of these landings ever went as planned. You just went in. All I can recall is this feeling that we were doing our job. I suddenly realised on the way across the Channel that this was a very, very big thing. There was this huge armada – and most of it seemed to be behind us."

The ramps went down and the lads of the Dorset Regiment stormed ashore. They were in the first wave of the D-Day landings on Gold Beach.

"You can't begin to describe it," recalls Norman Horton, of Great Wyrley.

"Everything was blowing up. There was shrapnel and bodies everywhere. All you think about is yourself. All you can do is get across the beach and into cover as fast as possible."

The race over the sands took a matter of minutes. As part of the 50th Division, the Dorsets were chosen to lead the attack on Hitler's much-vaunted Atlantic Wall. At first, tanks could not be used. It was a classic infantry battle of sudden death and shredded nerves.

"There were snipers everywhere. You never knew where the enemy was. You'd be talking to a pal one day and the next day he'd be gone.

"There were different faces all the time as new men arrived to fill the gaps."

By the end of June 6, 1944, the 24-year-old private was dug in with his company at a village inland from Arromanches.

"We took that village and lost it six times," he said. "It was never a pushover."

Jim Drew, from Tipton, was a 20-year-old sergeant, also with the Dorset Regiment. "The ramp went down and we stepped out, right up to our chests in water," he said. "Some of our comrades just went straight under because of the equipment they were wearing. The sea was red with blood."

Pinned down by fire, his unit was saved by one of the 'Funnies', a flail tank which smashed a way through a minefield.

"Our orders were to get as far inland as we could to secure a bridgehead.

"We advanced faster than anyone thought. We were about three miles inland when suddenly shells from our own guns started dropping all around us. My company commander had his arm blown off and I was blown up with shrapnel all over me."

He was not expected to survive and spent a year in a military hospital.

The story of the 'Funnies' began with a tragedy. Two years before D-Day, the Allies' raid on Dieppe ended in disaster.

Clearly, infantry on a beach were sitting ducks.

So, a few months later, Major General Percy Hobart was brought out of retirement to devise a range of armoured vehicles to make the beaches safe.

The result was 'Hobart's Funnies,' a bizarre assortment of converted tanks designed to blow up pillboxes, cross gaps, lay bridges, detonate minefields and squirt flames.

Bill Hawkins, a blacksmith, from Rawnsley in peacetime, was the demolition expert on a Churchill tank 'Funny' put ashore on Juno Beach to destroy German gun positions. But as the tank struggled ashore, it sank in a flooded culvert. He and his Royal Engineers crew all survived and scrambled out. On the beach they huddled together for shelter. But a German mortar bomb found them. Four of the six were killed. Bill suffered an arm wound and lost his left eye and part of his cheek. For him, the war was over. For years he never told his wife, Joan, what had happened to him on D-Day. All was revealed in 1976 when the French authorities at Graye-sur-Mer recovered the rusting Churchill tank and mounted it on a plinth where it proudly overlooks the invasion beach. Bill was one of the guests-of-honour at the unveiling of the monument.

The day before D-Day, 20-year-old Charles Scott, from Quarry Bank, and his comrades in the East Riding Yeomanry were told they had a mere 25 per cent chance of surviving the next 48 hours. They were in the first wave to assault Sword Beach in amphibious tanks.

"The Navy were very good. We were dropped right on the beaches by the landing craft. To be honest, some of the lads were happy to be on the ground again because they had become sea sick. I don't think they quite understood what a horrific situation we were being dropped into. There was just so much action going on, planes and gliders all over the skies, some being shot down, somersaulting in the air before crashing into the ground or into the tanks."

A German 88mm gun shot down one of the British gliders. Retribution from the Yeomanry was swift and deadly.

"Immediately, nearly all of the squadron turned towards him and shot at him," Mr Scott said.

"There was no time to think about what you were doing. The only time you weren't afraid was when you were shooting, carrying out your orders. I saw so much bravery that day. The infantry and the airborne were so courageous."

Horace Hill, from Cradley, trained for months on one of the top-secret weapons which helped win D-Day He recalls the 'Funnies' with pride. As a sergeant in the 79th Armoured Division, he commanded a Churchill tank fitted with a vast 'bobbin' of steel-reinforced track. As the tank advanced, the bobbin unwound and the track turned treacherous clay and sand into a road fit for armies.

"We had been trained to go over, under or through any obstacle in our way. And that included demolishing anything up to 14 feet of concrete."

He was in the first wave, at 7.30am on D-Day. As the landing craft crunched on to the beach, a shell tore into the next craft, killing a colonel. Mr Hill recalls 'a few bodies lying around'.

But by the fortunes of war, he had been dropped in a quiet sector of the beach. His 'Funny' went forward into six feet of water and made straight for its allotted task. The only snag was a jammed bobbin. It was heaved into place by a group of soldiers and one war reporter. Sgt Cox erected a green windsock to mark Exit No 4, Mike Green Sector, Juno Beach. Job done.

Hitler's troops, using slave labour, had spent four years building the defences known as the Atlantic Wall to keep the Allies out. Horace Hill and thousands of his pals punched a hole through it in about half an hour.