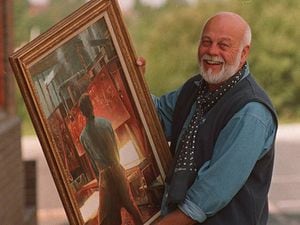

Black Country artist who painted for prime minister dies, aged 84

Tributes have been paid to an artist from the Black Country who moved to Cornwall but never forgot his industrial roots.

As an apprentice engineer in the Black Country, Nigel Hallard was surrounded by the sights, smells and sounds of the industry on which the area was built.

The heat from the roaring furnaces, the flying sparks, the aroma of molten metal being poured from one container to another as if it were a jug of milk.

But it was only when he moved to the idyllic Cornish fishing village of Mousehall that he appreciated the artistic beauty of what he left behind.

Nigel died in hospital on May 4, aged 84.

As a young man, trying to carve out a living at West Bromwich’s Brockhouse Drop Forge in the 1960s, it would never have occurred to him that people in Cornwall would want to buy paintings of his brutal surroundings. And he would certainly never have guessed that one of his works would be displayed by a future Prime Minister in his home at 10 Downing Street.

Nigel, who had also lived in Great Bridge and Dudley, moved to Cornwall in 1969 after falling in love with a local girl while on holiday.

“I was on holiday in Cornwall, and I met a friend of mine who was originally from Dudley, and he invited me to stay with him for a bit,” he recalled in a 2013 interview with the Express & Star.

“He said ‘I have got this girlfriend who won’t come out without her mate’, so I agreed to go out with them, it was a blind date. I married her a year later.”

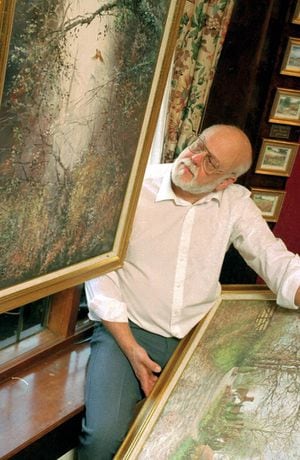

Realising that his chances of finding a job in engineering were limited in his new home, he decided to become a landscape painter, selling paintings of the Cornish seascape to visiting tourists.

For some years this provided him with a living, but as the traditional industries of the Black Country began to disappear in the 1980s, he started returning home to capture the region’s changing landscape on canvas.

His paintings quickly built up a following, attracting a number of high-profile commissions.

Former Prime Minister Sir John Major displayed one of his paintings – inside his old workplace at the Brockhouse drop forge – on the walls at Downing Street, while another was on show at the old Transport & General Workers’ Union offices in West Bromwich.

During the 1980s and 90s, Nigel held regular art exhibitions around the West Midlands, at venues such as the Stone Manor Hotel in Kidderminster and the former Moat House Hotel in West Bromwich.

One year he wanted to borrow the prime minister’s painting of Brockhouse for a Royal Society of Arts exhibition at the Adelphi buildings in the Strand.

“I spoke to the Prime Minister’s wife, and she offered to bring the painting to me, but I wanted to go to Downing Street to pick it up,” he said.

“I didn’t meet John Major, but I had a chat with his wife. The painting had been presented to him by the Chamber of Commerce, and it was on display in his flat.”

Nigel became a familiar sight around the Cornish coastline capturing the scenery, he said it was the industrial landscapes that particularly appealed as there were not many people who did them.

He said he was particularly fond of his paintings of the former Royal Brierley glassworks in Brierley Hill, which has since closed.

“I have done one of somebody changing the kiln. That is something that is gone forever now, it is part of our history.”

In 1989 he bought a second studio in Dinan, Brittany.

Nigel, who regularly returned to the West Midlands to check out his old haunts, said people failed to appreciate the potential of Black Country industry, or its importance to the economy.

“We’re still big engineers in the world, there’s a lot of engineering going on but we don’t get to hear about it,” he said in 2013. “When you had the big steel works at Round Oak, if you went in the pub at lunchtime the men would be in there, they would drink eight or nine pints just to replace the fluids they lost, they were big characters.

“You don’t see blokes walking down the street in their flat caps any more, but we’re still the fifth largest manufacturing country in the world, it’s just that people don’t know about it. They’ve been brainwashed.”

Nigel, who leaves widow Mary and son John, died in hospital on May 4.

Widow Mary said: “He was a tremendous character and had a marvellous career, he was very passionate about his work.”

Photographer Graham Gough, from Kinver, had known him for many years. “He was a lovely man and a great artist,” he said.