Kenya: The currency isn't money – it's sex

On the banks of Lake Victoria, women trade their bodies for fish they can sell at local markets. Rob Golledge visits Kisumu in Kenya...

The silhouettes of fishing boats are scattered across the horizon as the sun rises over Lake Victoria.

Men spend day and night in rickety wooden boats toiling on the hazardous water in the hunt for prized tilapia and Nile perch.

On the beaches women wait for the crafts to return so they can buy fish to sell at the market for a small profit.

But the currency is not money.

It's sex.

"Sometimes it can happen that there is no fish so someone gives you fish for friendship and you comply," says Rose Odundo, a 38-year-old widow at Luanda Kotieno beach in Siaya County.

"If you are a widow and have no one to support you it forces you to befriend a fisherman and exchange sexual favours so you become a priority customer."

The wrinkles on her face are cobwebbed and there is pain burning in her eyes. In the unrelenting heat she is exhausted. Exhausted physically and mentally.

"It breaks my heart. I cried, carried on, and continue to cry, "she says.

Sex-for-fish is a practice known locally as jaboya.

Africa will change you", a friend once told me many years ago.

"Your outlook will never be the same again," he warned.

I thought nothing of it and quickly forgot about his comments.

That was until last month.

A week after travelling across Kenya, without a doubt he was right.

My opinions had changed, my understanding had changed, I had changed.

Sat in the back of a white Land Cruiser – appropriately nicknamed The Beast – you look out on a country more diverse than you can ever imagine.

A land of unrivalled beauty, great creatures, and a million welcomes.

But also of Biblical poverty, misguided tradition, and archaic customs transposed in the modern world.

It is a place where the poor have access to mobile phones but not fresh water.

Where malaria nets are more useful to catch your dinner, than to sleep under and protect you from disease.

You cannot move for Coca-Cola signs and Premier League football shirts.

Yet half the population lives on around $1 a day.

In Western Kenya, the villagers are broadly content with their lot.

They have solid homes and want to farm their land and for their children to go to school.

They should be allowed to do that in the knowledge that they can get access to the right medical treatment when it is needed.

Kenya, like a lot of African countries, struggles with commercial exploitation and political corruption.

In my opinion it is not looking after its own.

What can be more of a priority than making sure your fellow man has access to clean water?

The work of NGOs and charities is playing a vital role.

Their work makes a real difference to real lives.

And unlike the actions of many governments, their work tries to solve the causes of problems not the symptoms.

Seldom would I spare a thought for the poor in Africa. We have tried for 60 years and failed, I erroneously thought.

Incredibly the solutions are simple. And we can all play a small part.

Every evening a slender rainbow sky of purple, orange, red and yellow sets over the Maasai Mara National Park. In the darkness you have only the stars for company.

They comfort and guide you.

We are those stars.

And we can make tomorrow a little bit brighter for the women of Lake Victoria.

For the fisherfolk of Lake Victoria it can be a deadly catch.

Jaboya is a major factor is the spread of HIV across Nyanza province as fishermen and fishmongers are both reluctant to reveal their HIV status to each other.

The lakeside counties of Homa Bay, Siaya and Kisumu have an infection rate up to four times the national average of six per cent.

The women have children to feed. Having sex with fishermen gets them priority over the supply and further sexual favours cover the cost of buying fish.

The women vendors can be as young as 14.

At the other end of the scale is 62-year-old Nera Aguko.

She has worked the beach for most of her life.

"We feel disempowered," she says.

"We feel shameful to work in this community where everyone knows what we do. It is shameful and embarrassing. We know that you should be faithful to husbands and this practice goes against scripture."

Karen Akoth, 33, adds: "You are forced to do it for money. If you can get more access to fish you do it.

"But it really hurts us. We are vulnerable. It is like walking with a shoe that doesn't fit – it is a pain we face every day but we cannot avoid it."

There are 22 beaches in Siaya county alone – each with hundreds of fishermen and fishmongers.

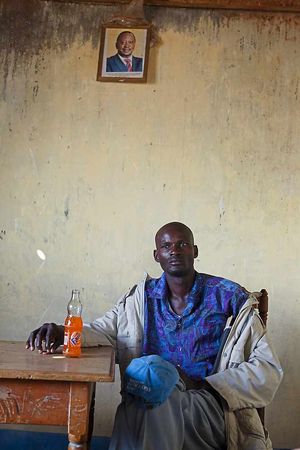

On Madundu beach I meet with the fishing management committee.

There are 350 users of the beach – 250 men and 50 women.

Life on the beach is complex.

"It is not changing," says Festo Otieno referring to jaboya.

"We know the risk. Because of poverty it is a force we have to deal with. It is a risk you take."

Mordecai Obala a member of the Madundu beach committee, adds: "We don't feel OK about it but we don't have an alternative."

Sex-for-fish is just one facet of a vicious cycle of poverty in western Kenya.

The fresh water in Lake Victoria has become polluted from factories.

Fish supply is low because of over-fishing and high competition.

Drug barons fuel young fishermen with cannabis, known locally as 'bhanga', and illegal extra-strong alcohol called 'chang'aa'.

Many of the fishermen believe it makes them immune to malaria because they cannot feel mosquito bites. The intoxication also sedates them from the harsh days and nights on the lake.

There are also migrating prostitutes who follow the fish trade around the lake which exacerbates the spread of HIV.

The biggest threat on the water is drowning. Contracting HIV is low on the fishermen's list of concerns.

The introduction of HIV drugs in some quarters are making the situation worse, according to some in the community.

"People are becoming very bold," says Mr Obala.

"Where they might have been cautious before, some know they can get the drugs and take the risk.

"Casual sex workers who come to the lake also bring a high risk of infection.

"The fishermen believe drugs will make them work for longer.

"There are condoms but when the fishermen are under the influence of drugs they won't use them. Others don't believe it feels the same and in some instances the cost of a condom is more than the woman will get from the fishermen.

"Fishermen will also pay more to do it without.

"Some are still afraid of them and some women fear they will get trapped inside." Underlying all these issues is poverty.

But how do you stop a cultural practice like jaboya which has been handed down from father to son for generations?

The fishermen and fishmongers believe small investment in infrastructure could eradicate some major problems facing these communities, including the sex-for-fish trade.

Getting electricity to these villages is seen as the first necessity.

The supply tends to stop around 1.8 miles (3km) from the beach.

The fish caught on the beach has a lifespan of 45 minutes before it starts to perish and rot.

It means large fish buying companies with refrigerated trucks can pay rock-bottom prices, knowing the fishermen have no one else to sell to.

A catch of 1kg (2lb 3oz) will be sold for 100 Kenyan shillings – 64p – but in restaurants a fillet of tilapia will cost 900 shillings (£5.78), meaning the big fish firms are able make large profits on the back of the fishermen's gruelling work.

"If we can get electricity we can refrigerate our fish," says Madundu beach committee vice-chairman George Ngria.

"That means we will not be forced to sell all the fish and can demand a better price.

"With a fairer price it means we can invest in getting boats for women to rent out to fishermen so they do not have to have sex to get fish."

Back at Luanda Kotieno beach, fishmonger Nera Aguko agrees.

Call the charity on 0845 7000 300

Donate online at christianaid.org.uk/christmas

She says: "If I have capability for a better shed to store fish I can build a better economy and more security for myself and not have to engage in sexual practices."

Christian Aid works with its local partner faith-based organisation ADS Nyanza to intervene in communities around Lake Victoria.

As well as running education programmes around HIV and training voluntary health workers to protect people with HIV from other rampant diseases like malaria, they are exploring new ways in working with the fishing communities they hope to resolve exploitation of the fish market to help clampdown the practice of jaboya.

The work of Christian Aid challenges inequitable gender and socio-cultural customs that hinders access to quality health for women, children and people living with HIV. Through dialogue with village elders and community leaders they are starting to change these traditions.

There are 1.3 million adults living in Kenya with HIV.

More than 370,000 of these live in the three counties of Homa Bay, Kisumu, and Siaya.

And the same three counties account for 30,000 new infections among adults every year, and 7,000 among children.

Tobias Aulo, health project coordinator at ADS Nyanza, says: "Talking about sex and sexuality is a taboo.

"Young people are vulnerable because parents don't talk about sexuality.

"It means the information they get is wrong."

Also part of the spread of HIV is the practice of wife inheritance.

When a man dies, his brother or close male relative will inherit his wife.

"Wife inheritance was historically a protective role where the man provided for his brother's wife and family.

"Sexual activity was not forced. But now it is being abused. It's no longer about providing, it is exploitative and diseases are spiralling out of control.

"In some cases if your husband dies and you don't want another one, they say you cannot stay on your own and impose a person on you. Women who say no can become ostracised."

Samuel Omondi, executive director of ADS Nyanza, said: "Sixty per cent of the people in this region are living below the poverty line.

"It is a very high burden, particularly HIV/AIDs. The region is a net importer of food. So we work with organisations like Christian Aid across three main areas.

"The first is to facilitate food security and bring food to the table.

"That is to bring good nutrition.

"The second is on economic empowerment. How can we get communities to get extra income. This can come through loans and saving groups to expand their businesses. Thirdly, and most importantly, it is about prevention of ill health.

"HIV/AIDS is one of the major problems around the shores of Lake Victoria. There are pools that give birth to mosquitoes so malaria is very big issue.

"We have 40 staff who work in communities to address these issues."

Through donations to Christian Aid, ADS Nyanza's work is starting to make a difference.

However, the NGO is appealing for extra funds this Christmas, so that it can reach more communities in the grip of poverty.

Kenya is home to east Africa's biggest economy.

But despite economic growth, the gap between poor and rich is growing – making the country one of the top 10 unequal societies in the world.

A quarter of the population lives on US$1 a day and two thirds on less than US$2.

As the great lake is shrouded in darkness, the fishermen have only the stars in raven black sky for company in the dead of the night.

Come sunrise, the women will be waiting again, willing to do what it takes to feed their children.

Little by little, the inhabitants around Lake Victoria are starting to understand the dangers involved with sex-for-fish.

But to change a lifestyle and customs bred out of poverty will take more than good will – that's the catch.

By Rob Golledge

Pictures courtesy of Christian Aid / Tom Pilston