From humble beginnings to huge success - 275 years of engineering

From tinplating and japanning to producing hi-tech components for the latest jet airliners and Formula 1 racing cars, it's all been in a day's work for the skilled craftsmen and women at what is now HS Marston over the last three centuries.

The company is now part of US-based United Technologies, one of the biggest engineering corporations in the world, but it can trace its roots back a staggering 275 years through a history that includes two world wars, the start of motorised transport and the birth of the Industrial Revolution.

Today 350 people work at the factory, on Wobaston Road, making heat exchangers such as oil coolers used on aircraft made by Boeing, Airbus and Bombardier, as well as military aircraft.

The same technology is also used on high performance racing cars, with Marston supplying virtually every Formula 1 team, as well as America's NASCAR and Indy racing teams.

It also makes pipes, manifolds and hoses used on aircraft for moving around liquids such as oil and hydraulic fluid.

And its workforce is now at the cutting edge of new technologies, using laminate materials and so-called 'additive manufacturing' – better known as 3D printing, where machines can produce solid objects from a digital computer file.

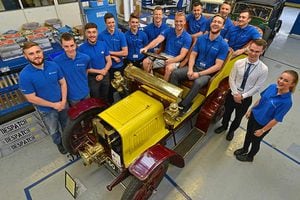

But the staff were given a chance to bask in three centuries of history as HS Marston held an exhibition at the factory to show off past products, from tinware plates to Sunbeam motorcycles and cars, as well as parts used in famous aircraft down the years, from the Mosquito and Wellington bombers of the Second World War to Concorde, the Harrier jump-jet and the swing-wing Tornado.For many of Marston's younger workers, it was the century-old motorcycles and cars that proved particularly fascinating as they were driven up and down the private road at the front of the factory.

1740: The Perry family established a metalware japanning business in Old Hall Workshops, Wolverhampton.

1790: Edward Perry founded Edward Perry & Son.

1836: John Marston was born in Ludlow, Shropshire.

1871: John Marston acquired control of Edward Perry & Son renaming it John Marston & Co.

1887: First Sunbeam bicycle made.

1900: First Sunbeam car The Mabley Sunbeam and associated radiators manufactured.

1905: Formation of the Sunbeam Motor Car Company – making John Marston one of the country's biggest vehicle radiator manufacturers. Customers include Rolls-Royce, Austin, Standard, Wolsey and Vauxhall.

1914-18: Motorcycles, motor cars and aircraft engines were produced for use in the First World War.

1919-1920: John Marston Ltd bought by Kynochs, part of Nobel Industries.

1926: Nobel Industries became part of the new ICI.

1935: Sunbeam went into receivership, bought by the Rootes Group. The aero engineering business continued.

1938-45: As well as radiators the company manufactured oil coolers, aluminium aircraft fuel tanks and undercarriage legs to support the war effort.

1978: Introduction of the vacuum brazing technique for aircraft heat exchangers.

1983: Palmer Aero Products acquired from BTR and moved from London to Wolverhampton. Some of the products of the newly renamed Marston Palmer included flexible hoses, ducting, couplings, filters, de-icers and electrical harnesses, which were all for aerospace use.

1985: Company name was changed to IMI Marston.

1999: Aerospace business of IMI Marston acquired by the American Hamilton Sundstrand group, a subsidiary of United Technologies Corporation (UTC) and HS Marston Aerospace Limited was established.

2001: Electronics cooling business acquired from IMI Marston to expand HS Marston heat transfer capabilities.

2012: United Technologies Corporation acquired Goodrich and formed UTC Aerospace Systems.

Two of the newest recruits are apprentices Jack Seaman and Sophie Wilson, both 17, who started work just 10 months ago.

"It's been really great working here, but it's been completely different to what you think its going to be like," said Sophie. "I always wanted to be an engineer and I'm absolutely loving it.

"I had considered being a jockey, because I love horses. I still ride, but engineering won out – it's always been my biggest love. It was my dream when I was at school – at St Peter's Collegiate – I was always getting my hands dirty working on something.

"I really like it and found I was really good at it. It really excited me. You just get such a sense of achievement working on an engineering project and making something.

"I've been working in the radiography department but now I'm in special projects doing machining."

Jack added: "I come from a family of engineers – my grandad and my uncles.

"My dad was the only one who wasn't an engineer. It was very competitive to get an apprenticeship place here at Marston's. There were just five places and about 150 applicants. Now I'm working on fluid management systems.

"It's great being part of a company with this sort of heritage, when you see the sort of things that have been made over time. This company's has been going 275 years and it makes you feel part of something very stable, that's going to be around in the future as well.

"And it's a company that has evolved, from making tin plates to making heat exchangers."

That pride is shared with more experienced workers like Peter Yates, who is also a member of the Sunbeam club and owns his own 1933 Sunbeam 250cc motorcycle. He also volunteers at the Black Country Living Museum, demonstrating the motorbikes.

Casting his eyes over the bikes on display at the factory, he said: "The oldest one here is probably from 1913.

"There's one from 1916 that I've ridden, which was an experience. A bit different from a modern bike.

"We also have the 1903 Sunbeam car, Fifinella. It's still running – we took it on the London to Brighton run in 2013."

Many of the vehicles and products on display were on loan from the Black Country Living Museum and the Marston Heritage Trust.

"The factory used to have most of them on display at its own heritage centre but they were bought by the museum about 10 years ago.

HS Marston traces its roots back to the Perry family who produced metalware at the Old Hall workshops in Wolverhampton in 1740.

Old Hall was a moated Elizabethan former manor house, standing in what is now Old Hall street in the city centre, site of the present Central Library.

For around a century is was one of the largest factories in the Midlands for 'japanning' – the process of putting a decorative black enamel coating on objects that mimicked the lacquered goods from Japan. The Perry family produced japanning and tinware, such as plates and cups, and their success led to the formation of the company Edward Perry & Son in 1790.

John Marston – the man whose name is still proudly emblazoned on the company's factory and literature – was born in Ludlow in 1836 and at 15 was apprenticed into the Perry business.

He went on to set up his own tinware and japanning company, later buying up the Perry business.

But he had an eye on the future. As japanware started to lose popularity, in the 1880s, John Marston – a keen cyclist – launched bike production in 1887 under the name Sunbeam.

John Marston, who served as mayor of Wolverhampton and as an alderman, also launched car production at Sunbeamland, the company's huge factory on the outskirts of the city centre, swifly followed by motorcycles.

With their distinctive black and yellow paintwork, the vehicles proved popular. In the First World War Sunbeam produced motorcycles for the Army as well as aircraft engines for the fledgling Royal Flying Corp – later the RAF. Those engines also carried the airship R34 on the first double crossing of the Atlantic.

Between the wars the Sunbeam name was on cars that took the world land speed record, while the 1,000 hp streamlined car dubbed The Slug by the workforce was the first to break the 200mph barrier, at Daytona Beach, Florida, with the great Henry Segrave at the wheel.

The car and motorcycle arm of the business did not survive the Great Depression between the wars, but Marston's went on, making aircraft engine radiators and self-sealing fuel tanks that helped many crippled aircraft make it safely back to base from missions during the Second World War.

The company had moved to Wobaston Road as it geared up for war production, and has remained there ever since. But that will change soon. Over the next year it will move to share the site of its UTC Aerospace Systems sister company on Stafford Road.

But managing director David Danger said HS Marston will retain its identity, as a company who's products have become a byword for technical innovation and reliability.

At the exhibition day he welcomed a group of former staff, known as Old Marstonians, as well as UTC colleagues from across Europe and senior executives from the USA who had been attending the Paris Air Show.

Mr Danger said the company had been started when George II was on the throne, Walpole had been Prime Minister 'and the United States was still a loyal British colony'.

And he said the company's continuing success was due to the skill, innovation and quality of its generations of employees.

His comments were echoed by Tom Pelland, president of the UTC Aerospace Systems engine and environmental control systems business, of which HS Marston is now a part.

Mr Pelland also praised Marston and its employees for their ability to adapt over the years to customers' changing needs.

With its 350 staff, HS Marston is part of one of the eight businesses that make up UTC Aerospace Systems, itself part of the UTC group that includes Sikorsky helicopters, Pratt & Whitney jet engines, a building and industrial systems arm that includes Otis lifts, altogether employing around 211,500 people around the world and with sales of over £40 billion a year.

Among those showing the the guests around were the company's two longest-serving employees. Nigel Ormerod and Kevin Dawson, both joined as 16-year-old apprentices on August 19, 1968.

Nigel is now the company's human resources director, while Kevin heads the special products team. "That's anything that needs to be done quickly or is a short run," said Mr Dawson.

"So if a Formula 1 team needs a new part between races, we have around two weeks to turn it around."

As a result, while many of the staff were enjoying the chance to look around the exhibition, some of Kevin Dawson's team were hard at work on a special part for an aircraft that was stuck on the ground awaiting repairs.

Mr Ormerod said guests at the exhibition included members of football teams from UTC sites across Europe attending a competition Marston was hosting at Lilleshall.

He added: "We have colleagues here from France, Germany, Poland, around a dozen facilities, all taking part, so we thought we'd coincide this exhibition with their visit. And it gives us a chance to show off our engineering heritage here."