Rain of ruin: 70 years after atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki

More than 200,000 people in two Japanese cities were killed - and within a week the Second World War was over.

The nuclear age dawned when the US bombed Hiroshima 70 years ago today and Nagasaki three days later, bringing the conflict to a sudden and horrific end.

The attacks remain the only instances of nuclear weapons used in warfare and the devastation caused can still be seen today.

The 4,400kg bomb, nicknamed 'Little Boy', that was dropped on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945 flattened five square miles of the city in seconds and had the power of up to 15,000 tons of TNT.

Haunting 'shadows' on pavements and walls act as reminders of the innocent people who perished in the attacks, with their outlines scorched into the concrete where their bodies blocked the intense heat of the blasts.

It was the combination of rocket technology with the power of the nuclear bomb that introduced the concept of deterrence through a capacity for total destruction.

The Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs proved the immense power that could be unleashed by the splitting, or fission, of atom nuclei in a huge chain reaction. But scientists were also aware of the even greater destructive power that could be produced by the opposite process, the joining together, or fusion, of lightweight hydrogen atoms.

This reaction required the extreme temperatures found on the sun, and scientists believed that such heat could be achieved by a small atomic explosion. The theory was first tested by the Americans on November 1, 1952 and the resulting explosion was found to be 1,000 times more powerful than the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima.

Within months the Soviet Union successfully tested their own hydrogen device and the Cold War arms race gathered pace on both sides of the Iron Curtain with Britain, France and China joining the two superpowers with substantial nuclear arsenals.

Tensions reached a peak in 1962 when the Cuban Missile Crisis made nuclear war seem inevitable. The 13-day confrontation between the US and the Soviet Union was played out on television, with one in five Americans at one point believing the Third World War would break out.

As negotiations deteriorated, fears rose of an imminent conflict – but a resolution was found, and a direct line of communication was set up between Washington and Moscow. This, and the threat of destruction if one of these missiles is deployed, has helped to safeguard an uneasy peace across Europe for the past 50 years.

However increasing instability around the world and the advent of rogue dictators like Saddam Hussein, who did not fear large-scale destruction of their own country, reduced the power of nuclear weapons as a deterrent. There are still fears over the secret arsenals held by countries like Israel, which is thought to have 80 warheads.

Since a Cold War high in 1986, whenstockpiles of nuclear warheads topped 65,000, the main weapons states have reduced their arsenals considerably.

At least 100,000 died of radiation-related illnesses in the wake of the bombings and it took decades to rebuild the obliterated cities.

Debate has raged ever since over whether the bombings were necessary to win the war, with supporters arguing that the Japanese surrender just days later was justification enough.

When US B-29 bomber Enola Gay, flying at 9,150 metres, dropped the bomb on Hiroshima on August 6, it was the culmination of years of secret scientific developments.

Rapid advances in scientific theory between the late 1880s and the Second World War made the bombs possible, with physicists shattering long-held theories and breaking down barriers.

The key event in the process happened in 1938 when the uranium atom was finally split into two nearly equal parts, adding a neutron to create energy using nuclear fission'.

Within days scientists realised that here lay the basis for releasing on a large scale the vast energy of the atomic nucleus – and talk centred on the possibility of a 'super-bomb'.

It was discovered that neutrons both initiated fission and were produced by it. It was therefore possible that newly-created neutrons could then go on to start more fissions, creating more neutrons to cause more fissions and so on - causing a massive chain reaction.

However, intensive research proved that the means of transforming the new discovery into a terrifying weapon required enriched uranium, an excruciatingly complex and costly scientific process.

But, as the scale of the Nazi threat to the world became apparent, pressure mounted on governments in Britain and the United States to commit sizeable funds to a uranium bomb project.

The call was strengthened by the discovery in 1941 that by bombarding uranium with neutrons, an intensely radioactive element that had never existed before on earth could be produced - plutonium.

At this stage Britain led the way in developing an atomic bomb but, after US President Franklin Roosevelt was finally convinced to devote resources, the emphasis switched to the other side of the Atlantic and the formation of the Manhattan Project under the command of Brigadier General Leslie R Groves.

It became the most expensive single programme ever financed by public funds and the project's range of factories and laboratories grew to be as large as the entire US car industry.

By the end of 1942 three huge 'atom cities' had been created, yet everything about them remained top secret.

They were known only by their codenames – Site W was Hanford, Washington, Site X was Oak Ridge, Tennessee, and Site Y was Los Alamos, New Mexico where the bombs were developed.

Roosevelt and Churchill finally reached agreement for the best British scientists to join the Manhattan Project and before long a total of 150,000 people were involved in the various parts of the programme.

The war in Europe was over by May 8, 1945, but with Japan's refusal to accept the Allies' demands for unconditional surrender, the Pacific War dragged on.

America, Britain and China called for the unconditional surrender of the Japanese armed forces in the Potsdam Declaration on July 26, 1945, or face 'prompt and utter destruction'.

So the nuclear developments continued as the Allied forces' secret weapon.

Scientists had few doubts that the uranium bomb Little Boy would explode successfully but there were doubts about the more complex plutonium bomb, which was called Fat Man - after Winston Churchill.

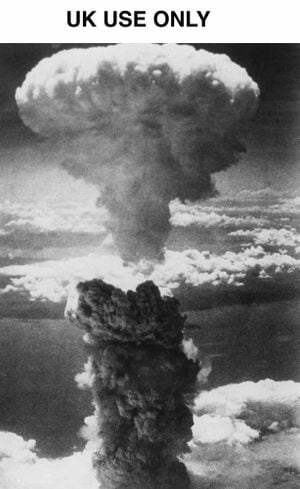

At 5.30am on the morning of July 16, 1945 all doubts were erased when, in a make-or-break test, the Fat Man erupted into the now familiar fireball and mushroom cloud in the first-ever explosion of an atomic weapon in the Alamogordo Desert in New Mexico.

There were more than 140,000 men being detained in Japanese prisoner of war camps and of these, one in three died from the conditions they were subjected to.

A lack of food and diseases with no prospect of any medicines to treat them meant the men were left emaciated and facing a slow, painful death.

But those that were left behind when the bombs dropped knew their lives had been saved and that they would once again see their families.

The horrors of being trapped in the camps haunted those men for years to come and many of them refused to speak about their experiences.

Camps were encircled with barbed wire or high wooden fencing and anyone brave enough to attempt an escape would be executed in front of other prisoners.

Sometime other innocent inmates were killed as a punishment for their friend's escape bid.

The men were regularly subjected to vicious beatings that left them in severe pain, made even worse when they had to walk for miles to carry out hours of manual labour.

Those sent to build the Burma-Thailand railway endured some of the worst conditions of any prisoners of war.

Some 61,000 men worked on the railroad, and 13,000 of those died.

Working from dawn to dusk they constructed the 260-mile line by hand, getting just one day off every 10 days.

Despite their relentless exertion, all they had to eat was rice and vegetables, so many became malnourished, while others were struck down by cholera.

Other men worked in mines, fields, shipyards and factories, surviving on barley and seaweed stew.

Among the starving hoardes on the railway was Netherton-born Ken Hill, who spent three-and-a-half years in captivity that reduced him to a near-skeleton.

It was only in recent years that the great grandfather opened up to family and friends about this horrific period of his life.

And he previously told the Express & Star that if it were not for the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, he would not have survived.

"That bomb saved our lives," he said.

Mr Hill, who joined the Territorial Army Field Workshop in June 1939 aged 18, added: "At last it was time to return home and we boarded a boat for Southampton. Our first meal on board was rice. There was almost a riot but the captain explained that doctors said as we'd eaten rice for three-and-a-half years our stomachs wouldn't initially be able to take rich foods. They gradually built us up to eat properly – and I haven't been able to eat rice since."

It was only after he returned he realised the anguish his parents, Ernie and Elsie had been through. They had barely received notice that Ken and his brother Geoff were prisoners of the Japanese.

George Hill, from Codsall, helped free prisoners of war from Changi Jail in Singapore after Victory in Japan had been declared.

Mr Hill, a private with the 1st Battalion of the Northamptonshire Regiment, got to know some of the prisoners of war that he released, and said they were in a 'terrible state'. And he admits, that despite the bombings leading to the end of the war he only remembers scenes of terrible suffering when he looks back.

Eight days later President Harry Truman issued orders for the dropping of an atom bomb on Japan as soon after August 3 as weather permitted.

There were widespread doubts, but on August 6 Little Boy was detonated over Hiroshima.

Announcing the bombing to the American people Truemans said: "We are now prepared to obliterate more rapidly and completely every productive enterprise the Japanese have above ground in any city.

"We shall destroy their docks, their factories, and their communications. Let there be no mistake; we shall completely destroy Japan's power to make war.

"It was to spare the Japanese people from utter destruction that the ultimatum of July 26 was issued at Potsdam. Their leaders promptly rejected that ultimatum. If they do not now accept our terms they may expect a rain of ruin from the air, the like of which has never been seen on this earth."

Fat Man was dropped on Nagasaki three days later and Japan rapidly capitulated.

Some days later a Japanese journalist arrived at what had been one of western Japan's biggest cities and reported: "There was a sweeping view, right to the mountains, north, south and east - the city had vanished.''

People on the ground in both cities described seeing a 'pika' or brilliant flash of light followed by a 'don', a loud booming sound.

Crowds of people were seen sitting among the rubble, gazing in disbelief at what remained of their surroundings. And police officers were dousing schoolchildren with cooking oil to help soothe the pain of their burns.

Around 62,000 of the city's 90,000 buildings had been destroyed.

Only the frameworks of those made from reinforced concrete to survive earthquakes remained.

The landmark Prefectural Industrial Promotional Hall, now commonly known as the Genbaku (A-bomb) dome, was the most notable surviving building, though it was only 500ft from ground zero.

The ruin was named Hiroshima Peace Memorial and was made a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1996 despite the objections of the US and China leaders, who argued other Asian nations had suffered the greatest casualties and that focussing on Japan as victims 'lacked historical perspective'.

In the immediate aftermath of the bombings, the world learned in awe of the terrifying new nuclear weapon, unaware that it had been years in the making.

And the extent of the devastation soon became clear, with a significant proportion of the population being wiped out.

Within the first four months of the bombings, up to 166,000 people in Hiroshima and 80,000 in Nagasaki died from the effects of the attacks.

Around half of the deaths in each city happened on the first day. During the following months, large numbers died from the effect of burns, radiation sickness, and other injuries, made worse by illness and malnutrition.

In both cities, most of the dead were civilians, although Hiroshima had a sizeable military garrison.

Around the time of the bombing of Nagasaki, the Soviet Union declared war on Japan after Stalin had agreed to back up the Allied bombardment.

But on August 15, Japan announced its surrender to the Allies - now celebrated as Victory in Japan Day.

Emperor Hirohito made an announcement to the Japanese nation the next day, and his harrowing words painted a picture of a nation that had been almost obliterated.

He said: "The enemy now possesses a new and terrible weapon with the power to destroy many innocent lives and do incalculable damage.

"Should we continue to fight, not only would it result in an ultimate collapse and obliteration of the Japanese nation, but also it would lead to the total extinction of human civilization."

And on September 2, he signed the instrument of surrender, effectively ending the Second World War.

It was clear the cities would never be the same again, but gradually they began to rebuild.

After the dead had been buried and the wounded had been sent to whatever medical facilities were available, the task of surveying and clearing the vast fields of rubble and debris took almost two years.

First, the rubble was cleared from the major streets, allowing trucks and heavy equipment better access to the site.

By March 1946, the main roads had been cleared of debris, and many of the ruined buildings were demolished and cleared away.

The work began to restore the infrastructure necessary to rebuild the city, such as water and sewage lines, electricity and food distribution.

By August of 1947, two years after the bombing, the majority of those living in Hiroshima were still in temporary shelters, but there were stores and homes being rebuilt already.

A small number of the City of Hiroshima staff were still in place after the attack, and worked hard to hand out food, and even distributed seeds for people to grow.

The pace of reconstruction was slow, as the city was estimated to require some 2 billion yen to rebuild, and the city's reconstruction budget in 1947 was only 56 million yen.

In the absence of Government investment, most of the early reconstruction in Hiroshima was done by residents themselves.

It was not until 1949, when new laws were drawn up by the country's leaders, that a formal plan was devised for rebuilding and ensuring survivors get proper medical care.

For four years Hiroshima and Nagasaki's people had lived in desperate conditions, finding shelter wherever they could, but soon a new sense of optimism swept across the cities and they began to look to the future.

References to the blasts are visible throughout the two cities to this day, including a memorial to the people who survived.

They are called 'hibakusha', a Japanese word that literally translates as 'explosion-affected people', and as of March 2014 there were 192,719, most of them living in Japan.

The memorials in Hiroshima and Nagasaki contain lists of the names of the hibakusha who are known to have died since the bombings.

Updated annually on the anniversaries of the bombings, as of August 2014 the memorials record the names of more than 450,000 hibakusha - 292,325 in Hiroshima and 165,409 in Nagasaki, including those who were unborn babies at the time of the attacks.

Hiroshima and Kunitachi, a small city in western Tokyo with a small population of A-bomb survivors, have tried to preserve the hibakusha legacy by setting up 'storyteller' courses open to people who have no direct experience of the attacks and no A-bomb survivors among their relatives.

Today, 70 years on The Hiroshima Municipal Government is expecting representatives from a record 100 countries to attend its annual ceremony, including U.S. Ambassador Caroline Kennedy, with survivors planning to release lanterns along the Motoyasu river – where thousands fled to escape the heat of the nuclear blast – in memory of the dead.