Peter Rhodes on the joy of gin, hypocrisy over Windrush and a great summer for horse flies

THE pig-racing event described yesterday took place during a pub's beer and gin festival, a reminder of how popular gin has become.

I could not help noticing that the brilliant little village store in Corfe Castle boasts of having 100 brands of gin. This may answer an old question: what do folk in sleepy holiday villages do during the long, dark winters?

THE worms may be shrivelling and the frogs dehydrating but one species is having a vintage year. I give you the horse fly, that drab little lover of human flesh. A couple of days ago one drove its pointy thing deep into my knee. From past experience this will create a scab, to be prodded and picked for months to come and providing harmless entertainment as the nights draw in. A horse-fly bite, the gift that keeps on giving.

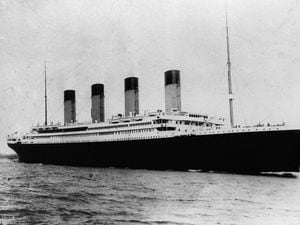

ANYONE else getting fed up of the Church of England rejoicing over the 70th anniversary of the arrival of SS Empire Windrush? The Church was no great friend of the West Indians who arrived in 1948. There are many accounts of black worshippers being turned away from white churches. Many of the institutions today piously celebrating Windrush were enthusiastic supporters of what was called the colour bar. It wasn't only wicked bosses and grasping landlords who behaved badly back then but trade unions, social clubs, police and, we have to admit it, the media. The reason immigration did not descend into rivers of blood in Britain was nothing to do with academics, clerics or politicians. It was down to the quiet decency of the working class who not only shared their streets and schools with newcomers but in time literally embraced them - which is why Britain's fastest growing racial group is mixed-race. Seventy years after Windrush the Establishment, which made life so hard for the West Indians, wraps itself in virtue while endlessly denouncing the "racism" of the British working class. Hypocrisy then, hypocrisy now.

I'VE spent years interviewing folk about their life and times and have heard the same phrase time after time: "I could write a book." But few do. And when Uncle Harry slips away, everyone suddenly realises they know nothing about his early years because they never asked the questions and Harry never wrote anything down. In my family, there is a gaping void about my father's experiences as an evacuee from 1939-43. He was billeted with an old lady called Aunt Maud who became his surrogate mother and shaped many of his views and values. But who was Aunt Maud? Nobody knows.

THE above item is a bit of a long intro to the fact that an old colleague of mine, John Phillpott, has just published a fine book about growing up in a Midlands village in the 1950s, from infancy to his first reporting job. It's a delightfully nostalgic and perceptive read called Beef Cubes and Burdock (Austin Macauley Publishers ). It's available from Amazon, and, if nothing else, it might stir you to pick up your own pen - before it's too late.