Lad's holiday that changed the face of the British pub

It wasn't the holiday Michael Hardman and his mates had planned. But when their week-long drinking session in Ireland began to go awry, they knew they had to do something.

There had been a whiff of discontent the night before, when they met for a warm-up session in Chester, getting a few in before they caught the ferry. But the beer they sampled was horrible. Flavourless, gassy, produced with no love whatsoever. It was time to take action.

“We were bitterly disappointed to discover that many of the places we called at in search of good beer – half a dozen pubs and a boat club – sold nothing of the sort. Instead of the flavoursome ale we loved, we were offered only gassy liquid from flashy bar-top dispensers.”

And when they finally reached the Emerald Isle, things got even worse.

“We had to content ourselves with Guinness, pint after pint of it,” he recalls.

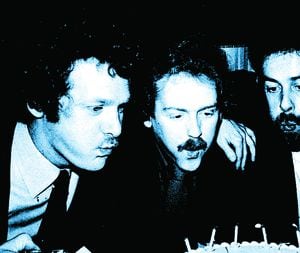

It was time to take action, and action they took. Deciding to salvage something from the holiday, former Express & Star journalist Michael and his mates decided to form a new drinking club to rectify the situation. And 50 years ago to this day Hardman and his three mates held the inaugural meeting of the Campaign for Real Ale.

Living in the heart of the West Midlands, Hardman had honed his taste buds on the great West Midlands ales such as Bathams, Holden’s and Banks’s, but when the lads crossed the Irish Sea, they found the choice distinctly underwhelming. And as the conversation during the jolly boys’ outing turned to jocular banter about how they would tackle the deteriorating quality of beer back home, the four – Michael, Graham Lees, Jim Makin and Bill Mellor, came up with a name for their new drinking club.

“We came up with the acronym Camra, which might mean the Campaign for something-beginning-with-R of Ale,” he says. “We couldn’t for the life of us think of what the missing word could be.

There was no such term as “real ale” back then. In fact it was only later, during conversations with pub landlords, that they realised what it was that differentiated the beer they liked – which was kept in casks – and the beer they didn’t which was served from pressurised kegs. Watney's Red Barrel – viewed almost as a swearword among many beer aficionados today – was the first keg beer, developed in the 1930s. Pasteurised and filtered to stop it going off, it was loved by landlords and wholesalers because it lasted a long time, required little nurturing, and using carbon dioxide to pressurise the barrel meant there was no need or a traditional long pull. By the early 1970s, it had pretty much taken over, with the traditional cask ales which were conditioned in the cellar apparently on the brink of dying out.

But while pressurised kegs may have been great news for the brewing giants, which at that time held a monopolistic stranglehold over the industry, all this filtration and pasteurisation meant that by the time the beer reached the punter, all the flavour had been filtered away.

Today, the Campaign for Real Ale – the “Real” bit was adopted later – has more than 170,000 members across the UK, and has been described as “the most successful consumer organisation in Europe.”

But there were few expectations during the new society’s first meeting at Europe’s most westerly pub, Kruger Kavanagh’s in County Kerry.

“Everyone, except the landlord’s mother and the four of us, spoke only Irish, so we decided it was as good a place as any to hold the first meeting of our secret society,” says Michael, now 74.

“Because I was the first to say anything, I became chairman. Graham Lees had a pen and a crumpled piece of paper, so he was secretary. Jim Makin was an office worker, an ideal treasurer, and Bill Mellor, who hadn’t offered to do anything else, was put in charge of organising events.”

Michael admits the foursome had no idea what the new group was set up to achieve, and it looked like it would fizzle out almost as quickly as the head on a pint of Watneys.

“We had no formal ambitions, no battle plan, no depth of knowledge of beer, no proper administrative experience,” he says. “Things seemed so hopeless after a few months that we had to call a special general meeting to keep the campaign alive."

The first annual meeting at the Rose Inn in Nuneaton on the anniversary of the Ireland trip, and after that things began to look up. Christopher Hutt, who was writing Death of the English Pub, and Frank Baillie, about to have his Beer Drinker’s Companion published, got to hear about the new club, and brought in a degree of professionalism and expertise. By the time of the second annual meeting, in 1973, the club had more than 1,000 members. A young DJ called Jeremy Beadle tagged along and was voted onto the executive committee, giving the new movement a plug on his BBC Radio London show.

Michael, who lived in both Wolverhampton and Erdington as a young man, remembers the area as a rare oasis in the desert of bland beer mediocrity.

“Back then there was a great choice of beers, there were the two Wolverhampton breweries, Banks’s and Springfield, and there were the Birmingham beers as well.

“But I also used to also enjoy going out to the Black Country, places like Brierley Hill, to the Bull & Bladder, where Bathams Brewery is, to Holden’s, and to The Old Swan in Netherton which is a beautiful pub.

“I think Wolverhampton and the Black Country was always a lot better than Birmingham, in Birmingham the Quaker movement imposed restrictions that pubs had to be at least a mile apart, which made pub crawls a nightmare unless you were in the city centre.”

Half a century on, the impact that Camra has made on the beer industry is there for all to see. In 1971, there were 150 breweries, whereas a report this week by accountants Hacker Young reported there were more than 3,000 – up by 200 on last year, despite pubs being mothballed during the lockdown. In 2014, Camra declared Britain to be the microbrewery capital of the world, with more breweries per head than any other country. While long-established breweries such as Springfield in Wolverhampton, Highgate in Walsall and Hanson's in Dudley have disappeared, there have been plenty of new, smaller breweries taking their place.

Michael’s work in preserving Britain’s ale heritage was recognised in 2009 when he was made an MBE.

“My son asked me how I got to meet the Queen by pouring beer down my neck,” he says with a chuckle. “I think he was quite impressed by that."

James Lynch, who organised Camra's first Great British Beer Festival, says: "Camra's greatest strength has always lain within the ranks of its membership.

"No other organisation I can think of has ever had such a broad appeal to people on every spectrum of society, bringing people together who would never otherwise have even passed the time of day with each other. So refreshing, a common cause that united everyone regardless."

Something we could certainly do with today...