'Once the statue toppling gets going, it’s going to be hard to know where to stop'

One hundred years from now there will be two statues in the whole of Britain, the rest having been ripped down in the great purges of the 2020s.

One will be that one of Billy Wright outside the ground of Premier League champions and FA Cup winners Wolverhampton Wanderers. The other will be of Eric Morecambe on the seafront at Morecambe.

Folk of the 22nd century will marvel at that far-off society, which cherished icons of sportspeople and comedians and destroyed everything else.

It’s like going through history books in your local library and tearing out pages you don’t like.

There’s a distinction to be drawn between modern statues despised in their own time, and those from that foreign country, the distant past. There has to come a point where they become historic artefacts, reminders – sometimes very uncomfortable reminders – of our history.

Don’t just blow them up or rip them down. That’s what the Taliban did to the ancient Bamiyan Buddhas. Or Islamic State did to ancient artifacts in Iraq.

Then there’s Oliver Cromwell and his merry band of Puritans and their 17th century orgy of destruction of those centuries-old icons and artworks which did not conform to their world view.

Oh, but that’s all different. Really? Apart from not agreeing with them, how, in principle?

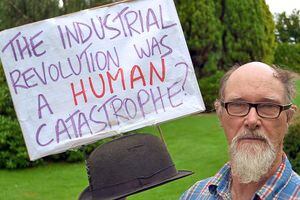

Expatriate Salopian Clive Booth used to make, and maybe still does, pilgrimages to Ironbridge from his home in Spain, holding up a placard saying “The Industrial Revolution was a Human Catastrophe.”

Where, he asked, were the monuments to the victims, the innumerable dead through industrial disease and dreadful living and working conditions.

The world famous Iron Bridge is a symbol of the Industrial Revolution. I think you can see where I’m going...

Let’s have some case studies.

I am not doing this gratuitously to trash reputations, but to demonstrate that once the statue toppling gets going, it’s going to be hard to know where to stop.

Admiral Nelson

When two sailors on the ship St George were sentenced to death for sodomy, other crew members protested, and four of them were hanged too, eyebrows being raised that it was done on a Sunday.

Nelson wrote a letter of congratulation and said: “Had it been Christmas Day instead of Sunday, I would have executed them.”

Also an adulterer.

In an infamous treacherous betrayal of a treaty of surrender, he handed over hundreds of liberals and intellectuals for execution at Naples.

Good job his statue is high up.

The Duke of Wellington

After the siege of Badajoz troops under his command indulged in a 72-hour orgy of violence and looting in which hundreds of Spanish civilians were killed. Men, women, and children were shot in the streets for sport.

Horrific though the riots were, Wellington thought they were useful as they would encourage other Spanish towns to surrender more readily.

After the capture of San Sebastian the town was ransacked by British troops, civilians massacred and women raped. The atrocity is marked in San Sebastian annually on August 31 with a silent candlelit procession.

Sir Winston Churchill

Any zealot worth his or her salt should be able to draw up a long charge sheet.

'Bomber' Harris

You will have heard about Dresden, but that was just one place of many.

Harris wrote in February 1945: “I do not personally regard the whole of the remaining cities of Germany as worth the bones of one British Grenadier.”

Harris was controversial even in his own day.

There was no specific medal awarded to the incredibly brave Bomber Command crews, and still isn’t, although a clasp was introduced in 2013.

John Lennon

Truly a modern icon, but not without major faults. Lennon’s attitude towards hitting women isn’t something he shied away from – in fact, he openly admitted it during a 1980 interview while insisting his earlier violence motivated his later calls for peace and love.

He wrote lyrics like: “I’d rather see you dead, little girl, Than to be with another man... You better run for your life if you can.”

Wilfred Owen

Virtually unknown as a poet in his own time.

His poetry however chimes with modern sensibilities and he is now seen as perhaps the greatest of the Great War poets. But a question arises from that.

If we give ourselves the right to re-evaluate people from the past and thrust greatness upon them, does the converse apply, that we also have the right to deny and remove the greatness that was thrust on people who were considered British heroes of their own times by their contemporaries?