"I am half eager, half fearful': Unseen letters from First World War officer's wife on the eve of the Somme

The letters home of a First World War officer from the west Midlands are filled with patriotism, passion, and resentment – and they have immortalised him.

Captain Alfred Bland's correspondence has been quoted in many of the best books about the Battle of the Somme. Yet his wife Violet, affectionately known as Lettie, to whom the letters were sent, has remained in the shadows.

Now the couple's descendants have allowed her letters to be seen, allowing others to discover what she was feeling during these cataclysmic events.

Only three of her letters sent to Alfred at the end of June 1916 and the beginning of July survive but they are enough to give an idea how the beginning of the Battle of the Somme looked to the wives of soldiers who held the fort for their children at home.

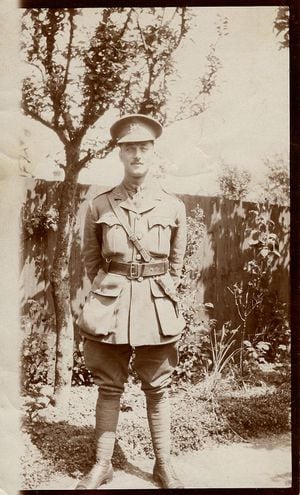

Alfred was 35, a former Kidderminster Grammar School pupil, who went on to study the classics at Oxford University and work as a civil servant in the Public Records Office in London whilst also teaching and writing academic articles about history. His family for two generations had made a living out of the drapery trade in Kidderminster.

Just as the war broke out, Alfred was offered a professorship at Melbourne University, Australia, but chose to enlist instead. He was assigned to the 22 Manchester Regiment, one of the ‘Pals’ regiments, and rose from private to captain within a year. Violet and their two children were living in Bexley, Kent, at the time.

On June 26, 1916, five days before the great attack began, Violet started one of her letters with the words: "Dearest. Are you still under the greenwood tree? (He had written to her saying that he and his unit had been resting safely to the rear of the front line in a beautiful wood). It sounded so good – too good to last. Did you go straight back to the trenches?

"Today the paper speaks of heavy shelling on the British front in the region of the Somme. You’ve been out of range of the guns, these days of rest haven’t you, though not out of hearing?"

The guns firing on the Somme were actually part of the pre-attack bombardment which those at the front hoped would make the planned advance a ‘walk over’. Unbeknown to those at home, the countdown to the the assault which would result in over 57,000 casualties, had already begun.

Violet did not restrict her letter to the momentous events unfolding in France, but also wrote about their children. She was thinking of taking one of their two sons to stay with his parents in Kidderminster which would take the pressure off her.

As if having her husband away was not worrying enough, Violet was also trying to cope with a diagnosis of cancer. In her letter she informed Alfred that her doctor had recommended that she should have 50 hours of radium.

Violet ended her letter: "All I want to know is that you are well and happy. Ever your loving wife, Lettie."

On the fateful first day of the battle, July 1, 1916, she wrote to him again. Ironically, it was one of the few times when Violet Bland believed her husband would be safe on the Western Front.

Little did she know that the middle-class life she had enjoyed before the war, as the wife of an academic and public servant, and during the war, as the wife of a respected officer, were about to end.

She was prompted to take up her pen on July 1 – in the radium room at Guy’s Hospital – after seeing a placard on the way to the hospital at London Bridge station proclaiming there had been a ‘British advance’.

Echoing what must have been the thoughts of many military wives at the time, she wrote: "I am half eager, half fearful. God knows we want this advance, but the cost.

"And you are to lead and love your greater responsibility, and the CO believes in you. This is all good. Your little rest came just in time and your men are fresher and more fit and the sunshine has been good to you. Heaven be praised for all.

"And do you believe and understand it when I tell you I am not worried about you even now. That I am as calm now as on the day when you said goodbye at Salisbury station.

"I shall look for a word from you still each week. But if you shall not be able to send, I shall interpret the silence rightly. This is probably a fierce time when everything will have to go except fighting."

Once again she talked about taking her sons to stay with their grandparents, and her hope that this would enable her to spend time with Alfred if he came home on leave. "There is such a large 'if' there unhappily," she wrote.

Sadly the 'if' was even bigger than she anticipated. By the time she wrote those lines, Alfred had already gone into battle, advancing at 7.30am with his battalion, and had died after being shot in the heart on the way to the Manchesters’ first objective, east of the Somme village of Mametz.

Almost cruelly, a short letter from Alfred reached Violet on July 5, four days after his death. Dated June 30, 1916, it consisted of just eight words: "My Darling, All my love for ever. Alfred" and was accompanied by a pressed flower, a forget-me-not.

Violet replied immediately: "My Darling, Your last little letter drew my tears. Bless you ever and always.

"Sometimes even here in Bexley we can hear the infinitely low and far away rumble of your guns. What must they be like with you?

"I’m proud too. The Manchesters are mentioned by name in the ‘brilliant exploit’ of the taking of Mametz."

She also referred to 'the comforting assurance that their casualties were not heavy.' She added: "It is a glorious start, surely the beginning of the end at last.

"You are my captain now first and foremost. I want you here safely in my arms, for are you not also my own dear, but more than this I want you to lead on to victory. Yes I do. I love you. Lettie."

These were the last words she wrote to Alfred, and here the trail goes cold.

It is known that a War Office telegram which started with the words: 'Deeply regret to inform you that Captain A.E. Bland 22nd Manchester Rgt was killed in action July 1st' reached the Bexley Post office at 9.16am on July 7.

It is not known how Violet reacted. All that is known from her family is that after he husband’s death, her cancer went into remission and she lived on until 1956. Like so many who lost husbands during the Great War, she never remarried.

Violet's story is told in the paperback edition of Hugh Sebag-Montefiore’s Somme: Into the Breach, which has just been published by Penguin, price £9.99.