Ben Crane on how his love of birds inspired book Blood Ties

This is his first interview. Ever. BBC World Service, Talk Radio and others are on Ben Crane’s hit list. But for now, they can wait. The Shropshire-based author of Blood Ties, which is published on October 4, only has time for his local newspaper.

And though Ben isn’t the normal household name you’ve come to expect from Weekend, don’t be put off – he has the most remarkable of stories. So pour yourself a cuppa, settle down and immerse yourself in a remarkable, real-life story that will teach you all you need to know about freedom and liberty, honesty and despair, happiness and redemption.

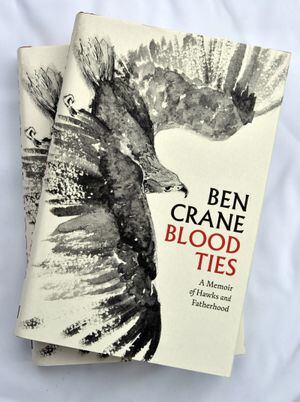

Ben’s first book is called Blood Ties. It’s about fatherhood, falconry and living with Asperger syndrome. Above all, it’s about the human condition. It took Ben three-and-a-half years to write and is a profoundly moving tale that narrates how reconnecting with nature helped Ben reconnect with people.

The synopsis goes something like this: Ben has always felt overwhelmed by a stream of observations and multiple interpretations of conversations – that’s what’s called ‘normal’ when you’re autistic. It was only in his adult life that he was diagnosed with Asperger’s, a condition suffered by around one in 100 people. A former teacher, Ben’s life suffered cataclysmic change when the birth of his son and redundancy plunged him into an emotional spiral.

He escaped to an isolated cottage in Shropshire and completely reengaged with nature, rehabilitating birds of prey, living off the land and sharing kill with his birds. The intensity, intimacy, care and connection necessary to rehabilitate those magnificent hunters ultimately helped him to reconnect with his son. His book throws in a bit of globe-trotting for good measure. Ben’s fascination with raptors has taken him around the world where he’s been able to learn more about the history and cultural differences among different raptor keepers. He’s encountered epic landscapes and vibrant communities along the way. And if that isn’t a sufficiently meaningful and evocative outline to Blood Ties, then you’re probably best sticking with a Jackie Collins or a Mills & Boon.

But let’s go back to the very start, the place where all the best stories begin. Ben was born and raised in the country. His life started somewhere near Acton Scott Farm Museum, not far from Church Stretton.

He adored the great outdoors from an early age and started learning about nature at the age of five or six. “I’ve always been interested in nature. It started off with fishing. I led a very rural life and I’d be out capturing snakes or poaching fish. Don’t tell the farmers.”

Ben found nature a very peaceful and safe environment, perfectly suited to his active imagination. It provided solace and adventure. “Nature is where my best memories are and where my best experiences are, even as an adult.”

He went to primary school in Church Stretton and secondary school in Shrewsbury before heading to Birmingham to complete a BA Hons in Art, Winchester for an MA and Cambridge for his teaching degree. He returned to Shropshire, teaching art at the Wakeman, in Shrewsbury, until it closed.

His interest in falconry happened during early adulthood. He was dating a girl who was interested in horses and as a birthday present she bought him a hawk walk. “As soon as I did that walk, I felt like an internal crack. It was like a lightning bolt inside. It was what I’d been searching for. It was so powerful and moving.”

It ignited a lifelong love of raptors. Though he was still working full time, he immersed himself into that world. A mentor helped him to understand the beauty of hawks and they’d go out and fly. Ben read everything he possibly could, learning more and more about his hobby while hunting around Much Wenlock and its hinterland.

“That passion was a gradual thing and it’s grown. Initially, I was just in awe of the fact a bird would fly back to me – a human being. And that sense of wonder never leaves me.

“But you come to see nature in a very different way when you’re hunting with a hawk. Hawks have to hunt to fulfil their basic instincts. So you have to learn to give yourself over to that primal urge, so that the bird is successful. Your senses become utterly focused when you’re out with a bird. Anything that may have been a concern or a worry in your life fades away. You become utterly and totally absorbed by the moment. The whole world looks totally different when you are flying your hawk and trying to hunt.”

Ben’s close contact with nature means he has an intimate understanding of its rhythms. It’s become a way of life, rather than a fashion or fad.

“It’s both relaxing but also intensely focused. The laws of the land stipulate what we must hunt, so we only ever hunt what is legally allowed. When the bird kills, nothing is wasted. I feed the hawk first, then myself.” Their diet consists of rabbit, pheasant, partridge but they eschew wild grey partridge and hare because they are less populous creatures and they do not wish to harm the balance of nature.

Though Ben’s background is in art, he taught himself how to be a better writer when he started flying birds of prey. It was such a profound experienced that he wanted to articulate it to others. “I’ve always been an artist and enjoyed that but I was awful at writing; at school, I got a Grade D in English. But the experience of keeping birds of prey was so profound that I wanted to write so that I could communicate it to others. I don’t have a TV and I don’t have internet or anything like that. So I sat down and wrote a book.”

And that’s how Blood Ties came about. Except it’s not. Because there’s another, equally compelling strand to Ben’s narrative. And it’s this. When his son, Elliot, was born, Ben struggled to connect. Though the symptoms of autism vary, one commonality is that autists find it difficult to forge emotional bonds with others. In Ben’s case, the difficulty arose with his son.

When the child was born eight years ago, Ben wasn’t at the birth. He didn’t experience the intense rush of love that many parents feel. Rather than marking the start of a golden era, his world turned black. “I had a mental breakdown. I found it psychologically difficult. I suffered quite terribly from it. The only way to recover was to walk away from my son and go and live in this little cottage, somewhere quite remote in Shropshire.”

And there Ben flew his hawks. And as he observed their graceful flight, primeval violence and survival instinct, he gradually began to recover. He wrote down his thoughts, to help him to make sense of the process. “Slowly but surely I got myself stable. I started with two sparrow hawks that I rehabilitate and released and I also trained a goshawk. At the same time, I came back into my son’s life. So Blood Ties connects my love of the countryside and explains how that taught me how to love my son. It’s about how I was able to love a species but didn’t love my son enough. And as I’m giving this interview, I’m looking after my son for a month and everything is great. So as the book progresses, those two narratives come together – for once, it’s a story with a happy ending.”

Ben initially planned to write a kid’s book. Who knows, he might have given a copy to his son. But his agent suggested a different sort of read – an adult exploration of the human condition, of love and loss, of the long road to redemption – and Ben agreed. “Slowly it developed out of that. It’s a very personal book and I was unsure about including a lot of the personal stuff in it. But that’s what we did and it took three-and-a-half years to complete.”

There are, of course, other books about falconry in circulation. Helen McDonald’s mesmerising book H is for Hawk won the Samuel Johnson Prize and Costa Book of the Year award among other honours, after being published in 2014.

“I haven’t read Helen McDonald’s book, though I’m aware of it, because I don’t want to be influenced by it. I’m sure she’s amazing. She loves raptors so she must be.”

Blood Ties provides a unique insight into the mind of someone with Asperger’s. It explains how the birth of Ben’s son was a cataclysm. “I didn’t experience the sort of things that other people feel – I hesitate to use the word ‘normal’. I’ve always struggled with the human world. My mind races perpetually – I have multiple thoughts at the same time. I find human society very confusing. There’s a lot of confusion and anxiety all of the time and it takes me a lot of effort to engage with other people; I’m very bad in social situations. But if I have a subject I can talk about like artwork or hawks, I can spend all day on it.

“I can paint for 16-20 hours a day. I’m focused on that stuff. And writing works for me. Once I’m in the zone, I’m in there for a long time. There are times when I wake up and I’ll spend the whole day trying to perfect a paragraph; I’ll be doing it until I go to bed. I’m relentless with it. Gradually, I’ve come to find writing a peaceful place. It’s as relaxing as going for a walk in the countryside.”

Ben is now happily reconciled with his son, who shares his fascination for birds of prey. It’s an interest that has taken Ben through Europe, to Texas, Pakistan and other parts of the globe. He’s met people who’ve been following the same discipline that has been passed down for more than 5,000 years in 65 different countries.

“I can get on a plane and go anywhere in the world and connect with a fellow falconer. On my travels to Pakistan, I met illiterate, subsistence farmers who were deeply religious but they welcomed me with open arms. I was only the second white Westerner they’d ever seen but they took me into their homes and fed me.”

Ben combines writing with painting and spending time with his son. Each day, he’ll spent two or three hours with his birds and dogs. “I send a pointer into the field and she will sniff a pheasant and lock solid, literally pointing in the right direction. Then the hawk will flush it out and chase.”

His present hawk is a bird that he’s hand-raised. It lives in his home – as a dog or cat might in other domestic circumstances. “The Pakistani guys are the same; their hawks even sleep with them. My hawk stays in his little box. I have the same sort of relationship that people might have with a dog. I almost find it easier to give myself over to the wellbeing of dogs and hawks than I do to other people – unless I know them very well, like my son.

“And that’s something I touch upon in the book. I’m aware that I can give myself over to animals and love them, so I realised that I must be able to do it with other things too – including humans. Animals have taught me a lot, certainly more than I’ve taught them.”

His relationship with his hawk is fascinating. If he approaches it in the wrong way, it will attack. “He wouldn’t kill me, but he’d do serious damage. But that’s because he is teaching me the limitations and parameters of what he needs. You have to get rid of your own ego when you have a hawk. You can’t bully or coerce. It has to be a reciprocal process. You put your human thoughts to the back of your head and work out what they are teaching you. It’s a reciprocal relationship. He teaches me about freedom. He teaches me not to be an arrogant human. The world is a bigger place than being a human being. The natural world is out there to experience and explore.”

Writing has helped to get Ben’s life back on track. He is moving forward with his son. And, with the publication of Blood Ties, he’s also written one of the most talked-about books of 2018.