Postcards from the frontline

These days they are associated with blue skies, white beaches and 'wish you were here' messages.

However, postcards reached the height of their popularity during the First World War when they were sent home from the battlefields of the Western Front.

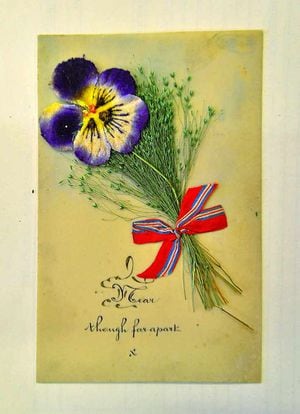

The silk-embroidered cards were made by French and Belgian women to sell as souvenirs to the hundreds of thousands of soldiers landing on their shores from across the Channel. A unique war-time industry was instantly created.

The strips of silk organza were originally hand-embroidered by women and girls in their homes or at refugee camps, but, as demand increased, production was moved to Parisian factories.

Batches of embroidered strips were sent for cutting and mounting onto postcards, which were then available to buy for a few francs each.

The postcards were hugely popular with British and American soldiers who bought them as mementos to send home to loved ones. It is estimated that some 10 million silk-embroidered postcards were made.

Some of those posted to anxious families in the West Midlands can now be found in the archives of the Staffordshire Regimental Museum in Lichfield.

Chief archivist Jeff Elson, aged 59, who served in the Staffordshire Regiment for six years, is one of a handful of volunteers at the archive. He describes the postcards as 'cherished reminders' of absent loved ones, many of whom did not survive, given pride of place on mantelpieces and dressers.

The highly-decorative cards would have made a significant dent in the pockets of the servicemen, who were paid just a shilling a day for their labours.

Mr Elson said: "One card would probably have taken two days' pay or more, depending on how elaborate it was, but the soldiers had little else to spend their money on. This was really big business – this is where postcards took off."

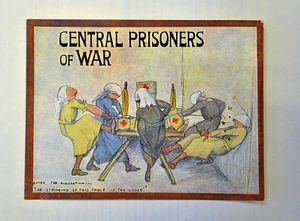

Images found on the front of the cards include forget-me-nots and pansies, bluebirds, patriotic messages and symbols such as the flags of the Allies, regimental crests and badges. The greetings, such as Absence Makes The Heart Grow Fonder, Hurrah For England and Remembrance From A Soldier, were beautifully stitched in brightly-coloured thread.

The vivid, picturesque cards would have been sent home, giving no indication of what the soldiers were experiencing, sparing mothers and wives from the true horrors of war.

In typically cheerful fashion, one of the museum exhibits reads: 'Just a line hoping this my card finds you quite well as I am in the pink at present. Give my best wishes to all at home – to dear brother and father – from your loving son Victor xxx'

Mr Elson, a retired Cannock police officer, said: "The messages were not hugely emotional. You find the soldiers often called their wives 'mother'. As well as commercial purposes, the cards were also used as propaganda. Some had pictures of dead Germans inside.

"When the war first started, the Express & Star and other local papers used to publish the lists of soldiers killed or wounded, but that stopped in 1915. The Wolverhampton battalions suffered quite heavy losses in the Battle of Loos in October 1915. It became bad for morale to continue publishing the names of the dead." Relatives back home sometimes received postcards featuring the statements 'I am well' and 'I am wounded' with the appropriate box ticked.

"Like all the post, the cards were censored. They could say very little of what was happening, partly because of the space and partly because if the soldier was captured, it might give away valuable information to the Germans."

Back home, the silk-embroidered cards were also proving popular. A typical British card would depict a women sitting at a writing desk with a picture of France in a thought bubble over her head. A different sort of postcard was also emerging. Cannock Chase was the location for two large camps, at Brocton and Rugeley.

Again, either individually or in groups, the men would visit local photographer's studios to have their pictures taken and made into postcards to be mailed to wives and girlfriends before the troops were shipped out to France. The post offices were kept busy, with many towns and villages starting tobacco funds.

There were also more general soldiers funds where residents would club together to send out much-needed items such as gloves, socks, balaclavas, lice powder, Beechams Powders and birthday cakes.

In return for the parcels from home, soldiers would make small gifts out of the 18lb artillery shells that were falling all around them. The soldiers could mould these weapons of destruction into beautifully-crafted models in the shape of aeroplanes, tanks, even three-sided matchbox holders.

Examples of these are on show in the museum. The trench art includes items carved from wood and even bone. After the war, tons of surplus materials were sold by the government and converted into souvenirs. And if French and Belgian businesses were benefiting, firms back home were not backward in grasping a commercial opportunity.

Shops in Cannock and Rugeley and across the West Midlands did a roaring trade in crestware churned out from the Potteries.

These models of tanks, machine guns and the like featured local regimental crests and were hugely popular. Many of these souvenirs are now highly collectable, particularly the postcards, known as 'WWI silks'. Because many were proudly displayed foryears in sitting rooms and bedsides, the cards often became sun-bleached and faded, or stained from exposure to coal dust and nicotine.

The most sought-aftertoday are those that are relatively clean with brightly-coloured silks, orunusual or unique images.

Mr Elson said: "The post was comforting, for those in the trenches and those at home.

"It meant you hadn't been forgotten.

The sentimental covers said it all."