Price falls could leave us deflated

After inflation turned negative this week, Business Editor Simon Penfold discovers that what the economy really needs is a little bit of positive inflation.

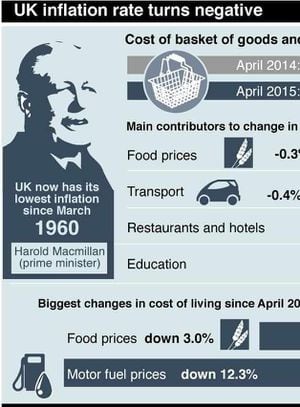

When official figures this week revealed that inflation had turned negative for the first time in more than half a century, Chancellor George Osborne hailed it as "good news for family budgets".

And, in the short term, it is.

We have all seen seen the price of petrol and diesel falling at the pump, while the cost of the weekly groceries has stayed low thanks to some bumper harvests and the price war between the big supermarkets and their discount rivals Aldi and Lidl.

But the low price of oil hasn't been good for everyone. The oil companies have laid off hundreds of workers as the low price makes it more expensive to get the stuff out of the ground.

Over the longer term, negative inflation can be very bad indeed.

If prices were to keep going down, we would all be inclined to put off spending on big items like furniture, TVs, cars, fridges and cookers, hoping to get a better deal later.

In turn, the companies making those goods will see their own income falling.

That could lead to them slowing down production, even laying off workers. It would certainly mean any chance of wage rises would disappear and some hard-pressed companies might even press for a pay cut.

It turns into a vicious circle, what economics call 'deflation', and the economy stagnates.

The last time we saw negative inflation was in the early 1960s, when Harold Macmillan was prime minister and Dwight Eisenhower was US president.

Then, as now, it was seen as a blip.

Mike Haynes, professor of international political economy at the University of Wolverhampton's Business School, said: "At the time the economy was actually chugging along quite nicely. You'd have to go back to the 1920s or 30s for real deflation and a sustained period of stagnation."

Back in March 1960 Elvis Presley was just finishing a two-year stint in the US Army, South African police shot and killed demonstrators in Sharpeville, Cliff Richard was in the pop charts, the Grand National had been televised for the first time and Wolverhampton Wanderers fans had high hopes of winning their third successive league title – they were pipped by Burnley by a single point but went on to win the FA Cup.

Inflation would bumble along at between zero and five per cent for the rest of the decade.

It wasn't until the 1970s that it became something to fear, as it soared beyond 25 per cent as the UK economy ran into crisis.

It was the rampant inflation of those years and the damage it did to both the economy and the everyday lives of ordinary people that has led to the Bank of England being given the job of keeping it under control.

The Bank, and its new governor Mark Carney, has the target of keeping inflation at about two per cent.

Graeme Chaplin, the Bank's agent for the West Midlands, explained: "The target is to keep inflation low and steady. By aiming for around two per cent it means that, even if we fall below that level, we will generally keep it above zero. We don't want to fall into deflation and the current drop is just a temporary blip. We expect it to be positive again next month.

"A low and steady level of inflation builds some growth into the economy but, more importantly, it builds stability.

And that is what we really want. It enables businesses and the Government to be able to plan for the future rather than worrying about volatility."

His boss, Mark Carney stressed last week that a temporary period of negative CPI – the consumer price index used to measure inflation – should not be mistaken for "deflation".

He said that three quarters of the reason inflation has fallen so far is the 40 per cent collapse in the price of oil, including lower prices at the pump, as well as lower food prices. At the same time the strong pound over the last two years has kept down the price of imported goods.

He predicted their impact would be 'short lived' and said a temporary period of falling prices "should not be mistaken for the potentially damaging process of widespread and persistent deflation."

"The economy is growing, unemployment is falling, earnings growth is improving and there is no evidence of household spending being delayed."

But others have expressed concern.

TUC general secretary Frances O'Grady said: "The first period of negative inflation in over half a century could turn out to be the canary in the mine, signalling that there's something very wrong with the recovery.

"And with the threat of deflation set to continue, the Chancellor's plans for extreme cuts risk putting the economy into more serious trouble."

And shadow chancellor Chris Leslie said: "Any relief for households is welcome, but this month's figures reflect global trends and doesn't change the reality that many are still struggling to pay the bills."

That concern is focused on something economics and central bankers call 'core inflation'. It strips out the big shifts in oil and food prices to try and give a clearer idea of what is really happening in the economy.

At 0.8 per cent in April, it was at its lowest level since March 2001.

Professor Mike Haynes said: "In economics the idea of noise and signal is quite popular. The April decline is noise – the key issue is what is the underlying signal. That is a very, very low inflation rate which is a concern.

"And negative inflation is not good for those with debt. A bit of inflation means you are earning more and it is easier to pay off your long-term debts, such as a mortgage, as time goes on. Low inflation makes that harder."

That works for Governments too – a bit of inflation means it can keep down the cost of paying off its deficit.

In the short term, we can all benefit from a spell of lower prices but most experts think it is unlikely to last. Oil prices have already started to creep up, and a litre of petrol was around 2p more in April than it was in March.

Experts reckon we will see inflation push up to around one per cent by the end of the year, still on the low side.

And, if it does go up, we may finally see that long-awaited hike in interest rates next year. Which will be good for long-suffering savers but is likely to come as an unwelcome shock to families with mortgages or companies with big debts after six years of rock-bottom repayment rates.