Black Country heroes of doomed Gallipoli

The men who fought at Gallipoli and survived are long-dead - but many carried the memories of the doomed campaign until their dying day.

Joining the tens of thousands of Australians and New Zealanders were troops from the Black Country.

Sam Cutts of Penn Common, was the last Black Country survivor of the campaign.

He turned 100 in 1990 and told the Express & Star of the orders he was given: Show no mercy.

He recalled: "One Turk came at me with his bayonet but when he was about five yards off he either stumbled or fainted so I stuck my bayonet in him. You see, we'd been told to kill or be killed, show no mercy, take no prisoners."

"We went ashore and there was one or two shots coming our way but nothing hit us. We'd only gone about 30 yards when we saw a Turkish patrol," he said. "And straight away our officers told us to dig in."

For the untried soldiers of the South Staffordshire Regiment's seventh battalion, it was the first mistake in a campaign littered with errors of judgment. For as they dug in at Suvla bay, the Turkish patrol escaped. By the time the battalion advanced, the Turks were waiting in force.

"It was terrible, terrible. The trenches were full of bodies," said Mr Cutts.

"The Turks had poisoned a well with two bodies. They were a cruel lot. They maimed some of our prisoners and sent them back. It was awful, the smell and the bluebottles on the bodies. The trench had a rocky bottom so we couldn't bury them. We just had to cover the bodies with sandbags. The Turks were on the hills and we were below, sitting ducks; the snipers were shooting us like rabbits. Twenty lads I knew personally were killed and we lost all our officers."

At dawn on April 25, 1915, Allied troops landed on the Gallipoli peninsula in what is today Turkey. Back then it was part of the Ottoman Empire and its people were fighting alongside Germany in the First World War.

Britain and its allies wanted to knock them out of the war. The plan was to land forces at Gallipoli, move inland and take the capital Constantinople, now Istanbul.

The plan, in which the Staffordshire Regiment played a full part, did not work, with disastrous consequences. The cost in human terms, was huge.

Allied success in the campaign could have weakened the enemy, allowed Britain and France to support Russia and helped to secure British strength in the Middle East. But success depended on Turkish opposition quickly crumbling. The plan had been hatched at the end of 1914 by Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty, with the hope that it would end the war early. The idea was that a new war front would be created and the enemy's attention would be diverted from the Western Front.

With the two sides locked into trench warfare in northern France, it was hoped that a battle fleet appearing off Istanbul would force Turkey's capitulation, secure a supply route to hard-pressed Russia and inspire the Balkan states to join the Allied war effort and eventually to attack Austria-Hungary, putting pressure on Germany. On February 19, British warships tried to force through the heavy Turkish defences of the Dardanelles, the entrance to the straits in northern Turkey, the key link between the Mediterranean and the Black Sea.

General Sir Ian Hamilton decided to make two landings, placing the British 29th Division at Cape Helles and the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) north of Gaba Tepe in an area later dubbed Anzac Cove.

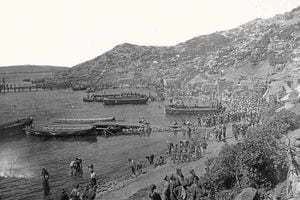

On April 25, 20,000 Australian and New Zealand volunteers landed at Anzac Cove. The first few days saw them scramble up the beach and dig themselves into the base of the cliffs.

Both landings were quickly contained by determined Ottoman troops and for eight long bloody months neither the British nor the Anzacs were able to advance. A captain in one of the first regiments to land wrote in his diary: "Off we went, the men cheering and dashed ashore with Z Company. We got it like anything, man after man behind me was shot down but they never wavered."

Trench warfare quickly took hold at Gallipoli, mirroring the fighting on the Western Front. At Anzac Cove it was particularly intensive.

Casualties in both locations mounted heavily and, in the heat, conditions rapidly deteriorated. Sickness was rampant, food quickly became inedible and there were vast swarms of black corpse flies.

In August a new assault was launched north of Anzac Cove. This attack, along with a fresh landing at Suvla Bay, quickly failed and stalemate returned. Finally, in December, it was decided to evacuate – first Anzac and Suvla, followed by Helles in January 1916.

The British government had thought a lot about the eventual sharing out of the Ottoman lands once the straits were captured, but very little about how the operation might actually be carried out.

The preparation was amateurish and the result a fiasco.

Around 44,000 British, French, ANZAC and Indian troops were killed at Gallipoli. Coming so early in the war, this huge loss of life had a powerful impact on those at home.

In the blazing Turkish summer the men of the South Staffs fell ill from infected water. As winter came they were so cold that some actually welcomed lice, as scratching them was the only way to keep warm.

Mr Cutts survived Gallipoli only to be wounded by shrapnel at Arras and by a bullet through the arm on the Somme. But his bitterest memories are of Gallipoli and he pins the blame on its architect. I blame Churchill. It was his fault . . . he made a blunder."

The Allied death toll in Gallipoli was more than 40,000, including two brothers who fought alongside Mr Cutts with the South Staffordshires, George and Jack Perks from Woodsetton, Dudley, who were killed on the same day at Gallipoli; their brother William perished later in the war.

Harry Hancy, known as Jim, was a sub lieutenant in the Royal Navy and was drafted in to drive a landing craft on the beach of Gallipoli alongside Australian marines.

He was the sole survivor from his vessel with the men coming under attack almost immediately after setting foot on the land which would become known as Anzac Cove.

He later lived in Shaw Road in Bushbury and was life president of the Wolverhampton North East Conservative Association and Bushbury Conservative Association.

Like many servicemen he never spoke of his time at war.

But on one rare occasion he opened up to former West Midlands County Councillor Charles Brueton.

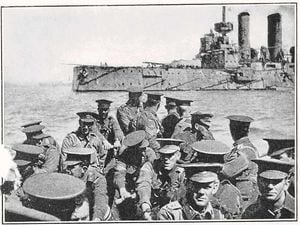

Mr Brueton, who lives in Tettenhall, said: "The Australian and New Zealand troops were taken to Gallipoli on various British warships which Jim was on.

"He was seconded to be with Australian marines and like other Britons he drove the landing craft up on to the beaches.

"There was not a shell, not anything when they approached the beach, he told me. But as soon as they got there and got off the boats all hell broke loose.

"They were running up the beach to get to the sand dunes.

"Jim made it to the sand dunes and told me all the noise seemed to stop from behind him.

"He said he looked around and all those who had come off his landing craft were dead.

"His words to me were 'why did God spare me?' He dug himself into the sand dunes and bullets were whizzing around everywhere. He managed to edge himself up to the rocks."

On January 30, 1920, Mr Hancy attended the first annual dinner of the Royal Naval Division Officers' Association.

He sent a menu around the tables to be signed by many of the distinguished guests – one of them was Winston Churchill.

"At that time Churchill was nervous, Jim told me," said Mr Brueton.

"The failure of Gallipoli had been attributed to him and Jim said Churchill made a speech where he was glad he had been made so welcome after so many men had died."

Mr Hancy lived alone in Wolverhampton, and died in the 1980s, aged in his 90s.

He gave the signed menu to Mr Brueton before he died.

"Jim told me about his time in Gallipoli and as far as I know he may have never spoken it to anyone else. Given the anniversary I wanted people to know that Wolverhampton had its own hero at Gallipoli, even if Jim would never have seen himself as one."

Heroic former Smethwick teacher Lieutenant Herbert James was awarded the Victoria Cross for his bravery during the Gallipoli campaign.

Born in Ladywood, Birmingham, in 1887 and educated at Smethwick Central School, Lt James was a teacher at Bearwood Road School and Brasshouse Lane School, both in Smethwick.

He joined the army in 1909 with the 21st Lancers and at the outbreak of the First World War, he was promoted and commissioned into the 4th Battalion the Worcestershire Regiment.

His outstanding acts of bravery at Gallipoli in 1915 included leading two successful counter attacks with next to no cover, after the failure of a major assault.

A few days later in a shower of bombs he saved a wounded colleague found lying among a heap of dead soldiers. He also secured the trench with a temporary defence of sand bags and dead bodies, to hold off the attacking Turks.

His VC citation read: "For most conspicuous bravery during the operations in the southern zone of the Gallipoli Peninsula. On June 28, 1915, when a portion of a regiment had been checked owing to all the officers being put out of action, Second-Lieutenant James, who belonged to a neighbouring unit, entirely on his own initiative gathered together a body of men and led them forward under heavy shell and rifle fire. He then returned, organised a second party, and again advanced. His gallant example put fresh life into the attack.

"On July 3, in the same locality, Second-Lieutenant James headed a party of bomb throwers up a Turkish communication trench, and after nearly all his bomb throwers had been killed or wounded he remained alone at the head of the trench and kept back the enemy single-handled till a barrier had been built behind him and the trench secured. He was throughout exposed to a murderous fire."

He was welcomed back to Birmingham in a special ceremony hosted by the city's Lord Mayor and subsequent Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain.

Lt James was wounded again on the Somme and, returning to France, in May 1917, he won the Military Cross near Amiens. He continued with his army service after the end of the First World War until failing health caused him to be placed on the retired list in March 1930.

But his life ended tragically when, in the 1950s, he was found by his landlord lying in his flat unconscious – having suffered a seizure six days earlier.

Gallipoli had been evacuated under extreme military secrecy in the latter part of December 1915. The only remaining troops in the area after this time were in the comparative safety of the medical base at Malta.

Leonard Hodgkins, of Halesowen, had been in the first battalions to go into the Dardanelles at the beginning of the Gallipoli campaign. He wrote 45 letters back home.

The first two are dated February 1915, in one he explains: "I have had a slight wound, but have got alright again, and expect to be going back to the Dardanelles in a day or two."

In his final letter from Malta is dated March 12, 1916, he wrote: "No doubt you will be surprised to learn that I am leaving Malta for Egypt in the course of a few days. We are only waiting for the boat which is expected tomorrow. So I may be in Egypt by the time you receive this letter.

"We are looking forward to a good time when we get in Egypt and I hope to see a few of the boys from Halesowen when I do get there."

Private William Johnson Barnett was in his 30s when he was killed in action at Gallipoli on August 25, 1915.

He had worked in insurance before enlisting with the King's Own Scottish Borderers and lived in Rugby Street, Wolverhampton, with his wife Elizabeth. His body was never recovered. He is now commemorated on the Helles Memorial, an obelisk on the tip of the Gallipoli peninsula in Turkey.

Robert Edwin Phillips, who was born in Hill Top, West Bromwich, was awarded the Victoria Cross for saving his mortally injured commanding officer from the battlefield near Kut, Mesopotamia, in 1917.

He had previously served in Suyla Bay, Gallipoli, as a Temporary 2nd Lieutenant in the 9th/13th Battalion of the Royal Warwickshire regiment, until being wounded in action on November 17, 1915, and after convalescence he rejoined his regiment, which in the meantime had moved to Mesopotamia.