Surrender brings peace at last: VJ Day 70th anniversary

Celebrations had already swept across Europe three months earlier – but on August 15, 1945, the Second World War was truly over.

Victory in Japan Day marked the final surrender of the Japanese forces to the Allies, led by Britain and America.

Tens of thousands of emaciated prisoners of war kept in squalid camps were set free.

But it was only a week since at least 129,000 people were killed by the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki – and it was already clear that the world would never again be the same.

The war had taken 45 million lives and the countries involved would take years to rebuild and move forward.

He was one of thousands of prisoners of war that struggled to survive on rations of rice, beetles and maggots while being subjected to the brutality of the Japanese guards who watched their every move.

Japan's surrender finally brought him freedom – but the effects of those years lasted a lifetime.

While thousands of his comrades died from exhaustion or cholera, Netherton-born Ken survived to start a new life after the war ended.

He married Brenda, raised two sons, lovingly tended his canalside garden in High Street, Swindon, near Dudley, and enjoyed a long career as an electrician. As the annual anniversaries of VJ Day came and went, they brought painful memories flooding back for him.

Ken joined the Territorial Army Field Workshop in June 1939, aged just 18, and at the end of 1941 he and his unit sailed to Singapore, where they set up a workshop to maintain guns.

In February 1942 the forces in Singapore surrendered to the Japanese after a siege, as soldiers scavenged in the streets in search of food and water. The corporal mechanic was imprisoned in the notorious Changi jail, near Singapore, where he briefly caught sight of his older brother, Staff Sgt Geoff Hill, who was also a PoW and survived his own hell in a prison camp in Borneo.

Ken said: "The Japanese showed us a shelf with five severed heads on it. They told us that it is what happens to looters."

Then followed a 250-mile march for Ken and his comrades through the jungle to the Burma border, where they started their slog to build the railway.

Ken faced many dangers in captivity – cholera, torture and even the fear of execution.

He said: "The Japanese guards would use the dreaded 'speedo' – a bamboo stick that they would hit people with as they yelled 'speedo, speedo,' to make them work faster. There were 7,000 of us to start with – but in the first six months 4,000 died and I don't think any more than 1,000 survived the war. I was lucky as I was young and fit. I remained healthy and that generally kept me safe."

It was the news of the atomic bomb attacks on Nagasaki and Hiroshima in August 1945 that brought about the end of the war in the Far East and secured the release of Ken and his comrades.

"That bomb saved our lives," he said.

Ken added: "At last it was time to return home and we boarded a boat for Southampton.

And in the short time since VE Day on May 8, Britain had entered a new era as Winston Churchill was voted out of office in favour of a Labour Government, while Germany was starting its reconstruction.

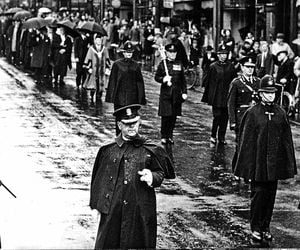

There were jubilant celebrations across the West Midlands in the wake of August 14's announcement, with crowds gathering in Queen Square, Wolverhampton.

But the joy of the conflict being over was also mixed widespread horror and fear at the means used to end it.

The nuclear bombs that devastated the two Japanese cities are seen as bringing the war to an abrupt halt – but thousands of Allied soldiers were on standby for a fresh attack on Japan.

The Parachute Regiment, for example, was in training for an airborne attack on Singapore, where the casualties would have run into thousands.

It never came to pass, though, and instead the prisoners of war that had been used as slaves could at last return home.

Their plight had not become common knowledge until British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden announced on January 28, 1945 in the House of Commons the 'barbarous treatment of British prisoners of war in Japanese hands'.

Hoardes of starving men built railways including the bridge over the River Kwai and the infamous 'death railway'.

Jack Jennings took part in the epic Battle of Singapore and suffered near-starvation on a Japanese prisoner-of-war camp before being sent to work on the railway line.

The 95-year-old retired joiner from Cradley Heath recently committed his memoirs to print in an online memoir.

He was part of the spirited defence of Adam Park, a strategically situated housing estate in the centre of the island, as part of the Cambridgeshires, a novice British infantry battalion which included many Black Country men.

They held their ground for four gruelling days until finally ordered by their commanders to lay down their arms.

It was the Allieds' last stand before the fall of Singapore, an event described by Prime Minister Winston Churchill as the 'worst disaster and largest capitulation in British history.'

Of the 100,000 men taken prisoner, 9,000 died building the Burma-Thailand railway.

Jack, who was just 20 when he left his home in Church Street, Old Hill, to answer the call of duty, was among 500 soldiers who were rounded up at Adam Park and taken to Changi prisoner of war camp, worn out and starving, where they were fed little more than a bowl of rice a day.

He was later among those moved to work on the Thai-Burma railway, featured in the classic film The Bridge Over The River Kwai, the line devised by Japan's Imperial Army at the height of the war to transport troops and supplies from Bangkok to Burma.

The line was completed in just a year but it cost the lives of around 13,000 POWs and 100,000 native labourers. He said: "You just got on with it. I never gave up hope. I made up my mind to forget about home.

"They were brutal in the camp but not as bad as when you were working on the railway. They beat you up for the slightest thing."

Ron Walker was in the RAF when war broke out and was shipped out to the Far East in 1941, serving with a squadron of Hurricane fighters.

But the RAF machines were outclassed and outnumbered by the Japanese Zero fighters. Some pilots flew to safety in India.

On March 8, 1942, leading aircraftsman Walker, aged just 23, was one of thousands of Allied servicemen taken prisoner.

In the three years that followed, a third of the PoWs in his group died of starvation, disease, ill-treatment or by casual execution. Three pilots caught trying to escape from the prisoner-of-war pen were executed by beheading. His group were put to work on the Indonesian isle of Ambon, building an airfield despite constant bombing. The work was backbreaking but any shirking was dealt with by a brutal beating.

By August 1945 Mr Walker and his weary, skeletal mates were back at the infamous Changi Jail, building foxholes and defence ditches. But they were never needed. News came, via hidden radio sets, that the Japanese had surrendered.

He added: "I'd come out to the Far East weighing 10st 11lbs. When we were liberated I was 5st 10lbs.

"I never expected to survive. If anyone had told me in 1945 that I'd still be around 60 years later, I would never have believed them."

Another prisoner of war at the Changi Jail, John Pratt of Sedgley was moved to Rangoon to be shipped home as the war ended. A young British Army signaller caught in the collapse of Singapore in February 1942, he was kept in captivity for more than three years.

He said: "My memory was shot to pieces. After being fettered for so long, all I wanted to do was to roam the country and visit some of the places I had been based."

He went on to marry and study engineering at London University, pursuing a career as a bridge-builder and metallurgist.

While their friends were being tortured and starved as prisoners, thousands of men were engaged in crucial battles that slowly turned the tide against the Japanese.

Joe Davies had already served as a driver in the Royal Army Service Corps in Arnhem when he returned to England after VE Day.

He was originally expected to join the forces in the Far East, until Hiroshima was targeted by an atomic bomb in August.

So instead he ended up in Palestine for a year. Mr Davies, of Tettenhall, who went on to become a police superintendent, joined the 6th Airborne Division for the end of the war.

"They were offering an extra two shillings a day, you couldn't turn that down," he said.

Mr Davies said that although VE Day is a crucial date in history, many men were still caught up in conflict for months afterwards.

"We knew there were lots of celebrations going on back home but it wasn't until everything came to an end in Japan in August that we knew it had all really ended," he said.

But life in the army continued for him until he left in August 1946 to join the police force.

Ron Mitchell, of Bridgnorth, was one of 130,000 British, Australian and Indian troops who surrendered at Singapore, imperial Britain's greatest fortress in the East.

The defeat of so many Allied troops by less than half that number of Japanese in February 1942 was one of the bitterest blows of the war.

Private Mitchell, a dispatch rider with the Singapore Volunteer Corps, was a prisoner of war for the next three and a half years.

On the day of the battle, one of his friends, also a dispatch rider, was captured by the advancing Japanese, tied to a tree and bayonetted to death.

He said: "You got the impression that there were very few Allied troops in Singapore.

"Then, when we were all marched off into captivity, well, I've never seen so many men."

When liberation came, Mr Mitchell was reunited with his parents but learned that his brother had perished in a Japanese prison camp in Borneo.

And back home, families and friends of soldiers were eagerly awaiting news of when they would be able to return.

Horace Shakespeare, of Moxley, was a seven-year-old growing up in Darlaston when the war ended.

He admits he cannot remember a thing about the party.

But he does retain vivid memories of the war.

He said: "My uncle was an Air Raid Precautions (ARP) warden and actually saw a bomb go off.

"And I remember All Saints church in Walsall Road getting bombed.

"That church saved a lot of houses by soaking up the blast. The blast went straight in through the door and turned the church upside down.

"But there was a little school building next door that lost just a few windows, and houses only 50 yards away were hardly damaged.

"That church saved lives."

One of these was Kohima, which from April to June 1944 was the scene of one of the most bitter and bloody battles of the Second World War.

For 18 months previously the British and Indian Fourteenth Army under General William Slim had been building up bases nearby at Dimapur and Imphal, ready for an offensive into Burma.

The Japanese Fifteenth Army was ordered to stop these preparations as part of a bigger offensive to destroy the British/Indian forces at Imphal, Naga Hills and Kohima.

As part of the massive Japanese assault, Kohima was attacked by an entire Japanese division. They were repulsed by British and Indian forces, which were cut off and had to be supplied by air drops.

The Japanese forces often infiltrated the British and Indian defences and there was vicious hand-to-hand fighting – but the Allies survived a 13-day siege.

Lord Mountbatten declared that it was 'probably one of the greatest battles in history', and as an example of 'naked unparalleled heroism' it was the 'the British/Indian Thermopylae'.

Among them was Jim Jones, from Warley, who was 16 when he joined up at the old Blue Gates in Smethwick and was assigned to the Royal Berkshire Regiment.

The Royal Berkshires were on the train for five days. Reaching Dimapur they were put on a lorry and went straight into action.

Mr Jones said: "We relieved the West Kents and had to fight our way in. It was terrible and, oh dear, there were bodies. You never see anything like it.

"We lost 300 men in a matter of two weeks, snipers and bayonet charges. That was how close it was at Kohima. It was closed like an island. We were cut off from Imphal. We had to be fed by parachutes, nothing else, water, everything. It was a case of three biscuits and a bully tin."

As the Japanese were forced back, Mr Jones and his platoon came to a river close to the River Irrawaddy. It was crossed by a railway bridge. The drop was 20ft and the only means of getting across was by walking on the sleepers. The platoon were ordered to go over the bridge at 4am and they reached the other side and began to dig in when the Japanese realised what had happened.

He said: "They let fly with everything. Air bursting shells. Grenades. Mortars. They even got in amongst the positions. I lost the two men beside me and lost the two men in the next pit.

"They was bayoneted. Anyway we lasted the night and we drove them off."

"We knew that we had gotta keep them out. Everybody. Because to be shot or captured was a terrible thought. You had to stand there. You know what you've got to do. You're a lance corporal and that's the trick. You've got to encourage. You've got to lead 'em."

Mr Jones was awarded the Military Medal for his bravery that night. After the success of the British and Indian armies at Kohima they forced the Japanese back in a fierce series of battles.

When Japan's Emperor Hirohito made his famous speech to his people confirming the surrender, there was a huge outpouring of relief in Britain as it dawned on everyone that the threat of attack had finally gone.

The Express & Star reported there were 'spontaneous rejoicings', adding: "Thousands of West Midlanders sang and danced in the streets, lit bonfires and fireworks."

As dusk fell, the sky was 'tinged with the glow of countless bonfires', the paper reported.

It added: "From the air the town probably looked as the German towns looked in news reels taken during RAF incendiary bomb raids."

Celebrations took place across the region, including trumpet players from the Royal Artillery Orchestra who played on the roof of Wolverhampton Civic Hall, in front of two huge illuminated letters spelling 'VJ'.